Losing “Our Louise” and Winning the Saxons’ Hearts: The Trials and Tribulations of Crown Prince Friedrich August of Saxony

Losing “Our Louise” and Winning the Saxons’ Hearts: The Trials and Tribulations of Crown Prince Friedrich August of Saxony

Frank Lorenz Müller

Whatever other failings he may have had, the chief prosecutor at the Landgericht in the Saxon city of Leipzig could recognise irony – especially when it was laid on with a trowel. In January 1903 he contacted the Saxon Ministry of Justice to accuse the Social Democrat Leipziger Volkszeitung of an act of Lèse-majesté (Majestätsbeleidigung) against the country’s Wettin dynasty. The paper, he reported, had described the royal heir, Crown Prince Friedrich August (1865-1932), as severely compromised by the recent scandal, but had predicted that he would nevertheless retain his place in the succession. Rather than abdicating, the article concluded, Friedrich August would surely “follow his father in his glorious reign.” Given the paper’s political leanings, the prosecutor concluded somewhat ponderously, such a description of the reign of his Majesty King Georg of Saxony (1832-1904) was clearly ironic and meant “to express the opposite of glorious.”

Upon this occasion, the Ministry of Justice decided not to pursue the matter further, but the Leipziger Volkszeitung was clearly skating on thin ice. When, a few weeks later, the paper had the temerity to observe that the “reputation of the king and the crown had greatly suffered in the wake of the recent marriage scandal,” the authorities responded promptly and without mercy. On 14 April 1903, the Ministry decided to prosecute Karl Albert Paul Lensch, the editor responsible for this outrage, and on 9 July a sentence of four months’ imprisonment was handed down to the unfortunate journalist.

The background to this tetchy watchfulness and somewhat trigger-happy flexing of Saxony’s authoritarian muscle was one of the greatest scandals to engulf European royalty during the Belle Époque. On 22 December 1902, after much of Europe had already been abuzz with rumours for several days, the Saxon government’s official publication, the Dresdner Journal, stiffly reported that Crown Princess Louise (1870-1947), the pregnant wife of Friedrich August and mother of their five children, had gone abroad “in a pathological moment of emotional turmoil, thus severing all the ties” that linked her to her Saxon family.

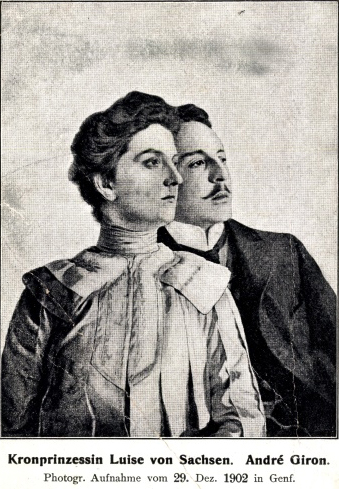

Eleven years after marrying the heir to the Saxon throne, the 33-year-old Habsburg princess had absconded during a visit to her ailing father in Salzburg. Louise crossed the border into republican Switzerland, where she was reunited with André Giron. This moustachioed Belgian had, until recently, been employed as her children’s French tutor. Showing herself in public with her young lover as they promenaded along the lakeside in Geneva and liberally dishing out the dirt about court life in Dresden in interviews to the world’s press, Louise quickly turned into veritable bugbear for the Saxon royal family.

The strictly legal side of the scandal was complex, but dealt with very promptly. A special court, convened by King Georg in accordance with the stipulations of the family statute (Hausgesetz) of the Wettin dynasty, swiftly found Louise guilty of several acts of adultery. The marriage was formally dissolved on 11 February 1903. This was a purely civil process, though, which had no bearing on the sacrament of marriage. The unfortunate Friedrich August, a good Catholic, was thus left in a state of matrimonial limbo and unable to remarry. Louise renounced all her rights and privileges as a former member of the royal family, but received a generous annual allowance. She was banned from ever returning to Saxony and denied access to her children. Arrangements were even made for her yet-to-be-born child to be handed over to her former family in due course – discreetly avoiding the obvious questions about the paternity.

These legal headaches were a mere trifle, though, compared to the public relations nightmare that was unfolding. For the future queen to run off with a lounge lizard and wash her dirty linen in public was bad enough. So the government-friendly papers tried their best to contain the damage. First they studiously ignored the story everyone and their dog was talking about and then they heaped all the blame on the allegedly hysterical and immoral Louise, an individual King Georg publicly condemned as a “deeply fallen woman”.

But to make matters worse, Louise immediately became the poster-girl for anyone who wanted to stick the knife into the Saxon government, into members of the Wettin monarchy, or into the monarchical principle more broadly. Armed to the teeth with many ghastly tales about her years spent at the Dresden court, radicals, democrats and socialists found that Louise’s story was a gift that just kept giving: a wronged yet mesmerising woman and doting mother cruelly cast aside by bitter and powerful figures at the court and in government. Soon “Our Louise”, the people’s princess, was born.

In February 1903, after Louise’s request to rush to the bedside of her sick son Friedrich Christian had been turned down, the radical Dresdener Rundschau adorned its front page with a facsimile of a letter the crown princess had written to a “simple, humble woman”. Thanking this “Good, Dear Woman” for her support, Louise affirmed the “infinite tenderness and love” she felt for her “5 little ones”. She would never leave them or “my Saxons, my people, to whom I am attached with the innermost love.” The “dear, simple people” of Saxony, she wrote, would not have to wait for her in vain. In its editorial, the Rundschau contrasted this “document of human greatness” with the goings on at the palace, where “courtly ritual, the great lie, and bony, ice-grey torpor are the almighty rulers – today as much as in the dark ages.”

A booklet entitled “The Truth about the Flight of the Crown Princess of Saxony. By an Insider”[1], rushed out within weeks of the event, offered a little more context. It described the estrangement between the Saxon people and their monarch that had gathered pace since the accession, in 1902, of the strictly catholic and distant King Georg. The king’s children had failed to compensate for their father’s lack of warmth, with Crown Prince Friedrich August caring only for hunting and the military. Louise, however, marked the only exception. She was a little ray of sunshine and popular with the people – and it was this, the anonymous author explained, which made her many enemies at court.

Claiming to apply a strictly Socialist mode of analysis, the Leipziger Volkszeitung identified an underlying structural reason for Louise’s elopement. “Monarchical marriage and family scandals have been a regular feature of monarchy,” it observed on 27 December 1902. It suggested that this was a case of nature wanting “to exact a revenge for the unnatural quality of an institution, in which a single individual is put in charge of the destiny of a whole nation.” Yet in spite of the Social Democrats’ protestations that they preferred a sober socialist analysis to cheap sensationalism, the Sächsische Arbeiter-Zeitung could not resist re-printing the long interview Louise had given to the Wiener Zeit. So Jesuit-ridden was the Dresden court, Louise explained, that even laughter was frowned upon. And the fate princesses had to endure was unbearably cruel, the princess insisted: ordered into a dynastic marriage and expected to be lifeless, without wishes and without a will of their own. Liberal papers joined in, too. “We all had taken her to our hearts,” the Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten, observed on Christmas Eve 1902: “this spirited, beautiful, charming, exalted woman, whose keen and unlimited concern for charity was well-known all over Dresden.”

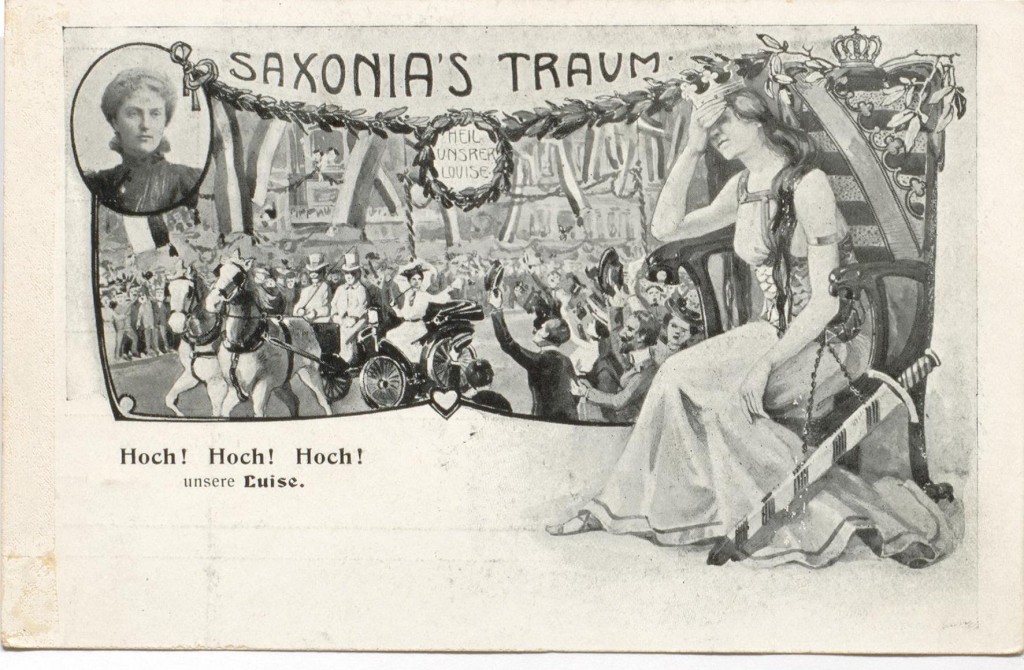

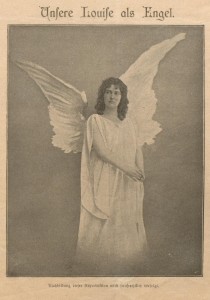

The cult of “Our Louise” grew and proved lasting. Soon, it spilled over into different media. Poems such as “And forgive us our trespasses”, which celebrated Louise’s “loving, motherly heart” or songs such as the Luisalied with its more or less tuneful celebration of “the pearl of Saxony” did their bit to keep the flame burning. But perhaps the most eye-catching aspect of the campaign was the use of visual images – mainly picture postcards – which soon flooded the country. They depicted the former crown princess surrounded by her former family or as “Saxony’s Dream”. And the buzz showed no sign of abating. In September 1904, the Dresdener Rundschau still opened with “Our Louise as an Angel” and a year later the same weekly lavishly celebrated her 35th birthday.

This cult of “Our Louise” turned into a most unpleasant thorn in the flesh of the monarchy. King Georg – soon lampooned as “Georg the Grisly” (Georg der Greuliche) for his less than winsome ways – was held responsible for the bleakness and bigotry of the court which had driven the princess away. His seemingly unforgiving attitude after Louise’s escape and his public denunciation of her as a “deeply fallen woman” also turned him and the government into targets of fierce attacks. “Sadly, King Georg is not surrounded by advisers that would convey to him the opinion of the people warts and all,” the Dresdener Rundschau observed in March 1903: “For otherwise this announcement could not have contained this embittering comment directed against Princess Louise.”

But neither King Georg nor his much-reviled minister Georg von Metzsch were the individual whose standing was most gravely affected by the Louise scandal. That dubious prize went to her husband of eleven years, the man the princess had left behind: Crown Prince Friedrich August. Louise spoke freely and excruciatingly about him. He had been too weak to protect her against those wielding real power at court, she told the Wiener Zeit, and the manner in which he showed his affection to her had been “too rough, and, with its complete lack of inhibition, had been torture” for her. She also denied that Friedrich August had any sense at all of culture, learning, music, literature and arts. As someone brought up by priests, she explained, the crown prince could not but regard such pursuits as dangerous and sinful.

The experience of the of the unfortunate Karl Lensch, who spent the summer of 1903 behind bars, showed that Saxon papers had to be careful about criticising the crown prince too openly. The democratic Volkswacht, however, was published in Austria and thus laid freely – and unfairly – into Friedrich August, that “drunkard and randy skirt chaser” who was really to blame for the “deep fall of his unhappy wife.” To get a sense of the mood of the people, all the prince had to do was to go for a walk in Dresden – as was his common practice. For unlike before, when people in the streets welcomed him cordially and warmly, the Prussian envoy reported in February 1903, Friedrich August was now rarely greeted at all and had to suffer catcalls from a curious throng following him. Some deranged individuals even went as far as sending anonymous letters to court representatives such as the lawyer Dr Emil Körner, who had acted for the crown prince, and was now threatened with dynamite attacks if he continued to bother “the woman who now belongs to the people.”

Little in his trouble-free previous life could have prepared Friedrich August for this kind of crisis. Born in 1865, when his grandfather, King Johann (1801-73), was still on throne, Friedrich August’s youth had been almost entirely uneventful. Brought up by two strict Catholics, Prince Georg and his wife Maria-Anna (1843-84), he received a standard princely education, including the usual military stages as well as a couple of years at university. Amiable, physically fit and unencumbered by excessive intellectualism, Friedrich August became a keen hunter and horseman. He travelled widely and served as an aristocratic part-time officer, who was popular with his men. In 1891 he married the Archduchess Louise of Habsburg-Tuscany, a vivacious catholic princess from one of the most senior dynasties in Europe. The Saxon public received the newlyweds with great warmth, and the couple swiftly produced a flock of princes and princesses. The impressively fertile family idyll was proudly documented on picture postcards bought by those with a penchant for monarchical bliss.

In June 1902, Friedrich August’s uncle, the venerable King Albert of Saxony (1828-1902) died. The childless monarch was succeeded – to the surprise of some, who had hoped the crown might pass directly to the younger generation – by his elderly brother Georg. The new king, an ailing widower, did not enjoy a propitious start. Coming, as it did, in the middle of a severe recession, his decision to accept a significant uplift of the Civil List, paid to the crown out of public funds, struck several observers as ill-advised. Moreover, Georg’s demonstrative catholic piety was compared unfavourably with his predecessor’s more subtle religiosity. Friedrich August barely had six months to acquaint himself with his new role as crown prince when Louise went on the run and the scandal broke.

In response to the crisis triggered by the collapse of Friedrich August’s marriage and the triumph of the “Cult of Louise,” the Wettins pursued a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, the force of the monarchical state was employed to suppress it, and several cases of Lèse-Majesté were brought. Soon Bernhard Peters of the Dresdener Rundschau met the same fate as Karl Lensch before him. Four months imprisonment was the price he had to pay for publishing his tongue-in-cheek “Fairy Tale of the Princes, who didn’t Know how to Pray”. Beyond the borders of the kingdom, however, the power of the Saxon authorities was clearly limited. In April 1905 a trial in Stuttgart – brought against the editors of the satirical magazine Simplicissimus – ended in an embarrassing defeat for the Saxon prosecutors.

Even at home the legal course did not always run smoothly. Attempts by the police to stop the display and sale of postcards with images of Louise – an act, it was claimed, which demonstrated “crass tactlessness against the sensitivities of his Majesty the King” – eventually led to a class action by postcard sellers against the government. The police lost the case at the High Court in Dresden in August 1905 and the postcards could go on sale again, to howls of derision from the opposition press. Crown Prince Friedrich August clearly backed this component of the response. In October 1903 General Friedrich von Criegern, the prince’s chamberlain, informed the Dresden police that Friedrich August had not given permission for the dissemination of photographs showing him and his children together with his ex-wife and he now expressly forbade their reproduction. The courtier also informed the police that he had come across a few prints of the ghastly Louise-as-angel photograph in the palace. With the crown prince’s permission, he had destroyed them immediately. Nor did the repressive approach did stop in 1904, when Friedrich August succeeded to the throne.

But there was more than one string to the crown prince’s bow. In February 1903, the Prussian envoy had been anything but sanguine. It would take “a long time and an unusual adroitness, which sadly he does not possess,” for Friedrich August to regain “the affection of the masses,” Count Dönhoff predicted. But the crown prince would prove the sceptics wrong and successfully fought for his popularity. Taking on Louise at her own game, he threw himself into the role of loving father of a large brood, subjecting himself – and his children – to an ruthless public routine of tender family relations and folksy affability. His children would later remember the close attentions of the “omnipresent father,” who insisted on a daily and flawless pursuit of the royal family’s charm offensive, with mixed feelings. But the plan bore fruit. Slowly, but surely Friedrich August clawed his way back into the affections of “his” Saxons – helped, unwittingly, by Louise, whose re-marriage (in 1907 to a much younger Italian musician) and second divorce undermined what was left of her popular appeal.

The welcome Friedrich August received from the press upon his accession in the autumn of 1904 marked a first milestone. The politically non-affiliated Dresdner Anzeiger praised the new king for coping with Louise’s desertion of her family and noted how he had “dedicated himself, as a tender father, with re-doubled love and faithful care” to his motherless children. “For years, residents of Dresden and [of the summer retreat of] Wachwitz, have had the opportunity of greeting Prince Friedrich August and his jolly band of children on their many outings.” The liberal Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten similarly praised the new king’s generous attitude to his estranged wife, the “great love, with which he cares for his children” and his gregariousness (Leutseligkeit) – all of which had helped him to win the hearts of the Saxon people.

Two brief hagiographical lives of the new king, both published within months of his accession, mined the same emotional seam. Friedrich August is devoted to his children, Richard Stecher observed, and after the calamity of 1902 it was “from their joyful chatter, from their sparkling eyes that happiness again shone at him.” A second pamphlet confirmed that the king “visits the nursery frequently and happily; he supervises not only the training of the mind, but also ensures well-planned physical exercises.” The latter publication already contained what would eventually become the hallmark of public persona ascribed to King Friedrich August: a long anthology of humorous anecdotes illustrating the ruler’s down-to-earth character, his affability, generosity and native wit.[2]

Over the years, King Friedrich August morphed into a much-loved figure, widely perceived as a thoroughly likeable, largely non-political, quirky and somehow characteristically Saxon monarch. Mindful not to transgress the boundaries of a narrowly defined role as constitutional monarch and careful not to be associated with unpopular policies he took his duties seriously – especially that of public visibility and cultural patronage across his little realm. The historian Hellmut Kretzschmar has gone so far as to detect in Friedrich August a new “type of monarch-made-middle-class,” a phenomenon that could justify the hope that Germany’s monarchies might have undergone a process of democratic evolution. This remains speculation, though, since notwithstanding his personal popularity, the king of Saxony lost his crown in the strangely low-key revolution of 1918– along with all the other German monarchs.

A remarkably serene ex-king, Friedrich August remained a popular figure until his death in 1932 and beyond. Louise outlived him by 15 years. After a few restless years spent in Italy, England and Mallorca, she had settled in Belgium in 1912 after her second divorce. It was there, in her flat in Ixelles, a suburb of Brussels, that she died, penniless, in March 1947.

Further Reading:

Martina Fetting, Zum Selbstverständnis der letzten deutschen Monarchen (Frankfurt, 2012)

Simone Lässig/Karl Heinrich Pohl (eds), Sachsen im Kaiserreich (Dresden, 1997)

Louise of Tuscany: My Own Story (New York, 1911) – https://archive.org/details/myownstory01marigoog

Hellmut Kretzschmar, “Das sächsische Königtum im 19. Jahrhundert”, Historische Zeitschrift 170 (1950), 457-493

Frank-Lothar Kroll (ed.), Die Herrscher Sachsens. Markgrafen, Kurfürsten, Könige 1089-1918 (Munich, 2004)

James Retallack (ed.), Saxony in Germany History. Culture, Society, and Politics 1830-1933 (Ann Arbor, 2000)

[1] Die Wahrheit über die Flucht der Kronprinzessin von Sachsen. Von einem Eingeweihten (Rudolf Lebies Verlag: Dresden, 1903)

[2] Richard Stecher: König Friedrich August III. von Sachsen. Ein Lebensbild (Dresden, 1905), 22-3; König Friedrich August III. von Sachsen. Ein Lebensbild zusammengestellt nach dem „Kamerad“ (Dresden, 1905), 27.