A family affair and a tottering throne

Heidi Mehrkens

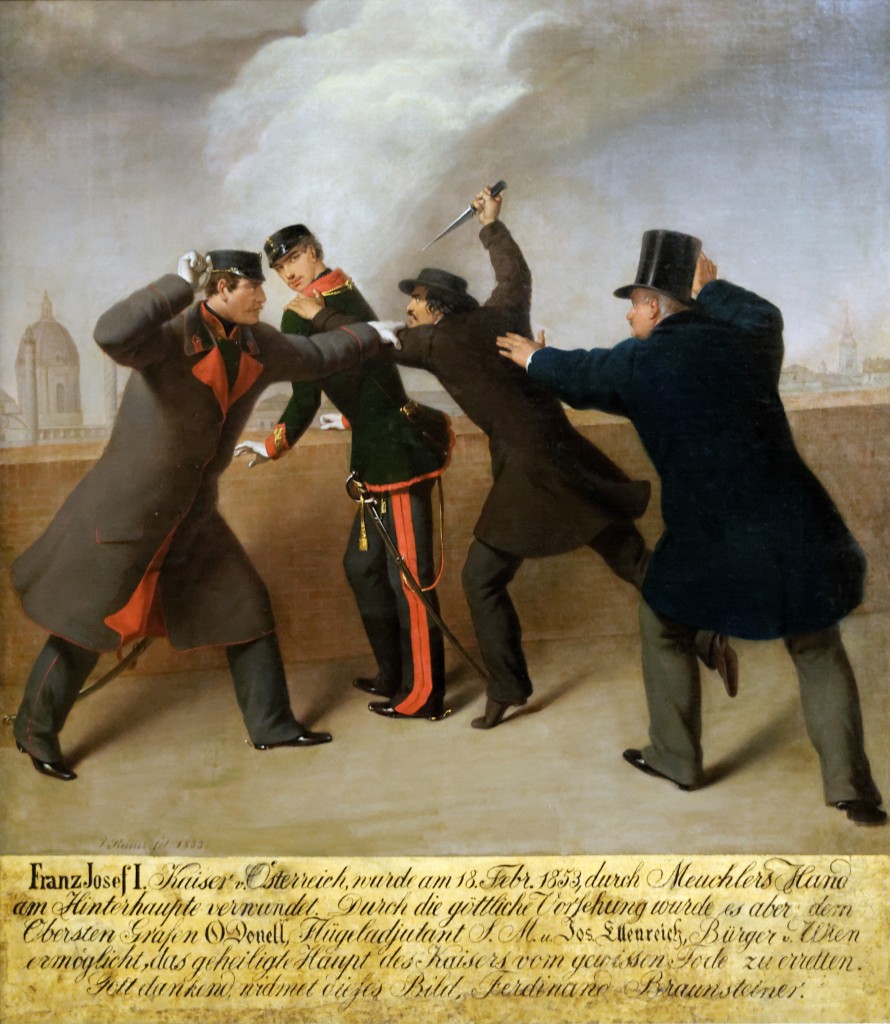

Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg would remember the day he almost became emperor of Austria. On 18 February 1853 his brother Franz Joseph who had been on the throne for five years, was nearly killed by the hand of a lad even younger than the 23-year-old monarch himself. The emperor enjoyed taking a stroll on Vienna’s city walls in the company of his aide-de-camp, Colonel Count O’Donnell. Luckily Franz Joseph was wearing his uniform of the Uhlans when the Hungarian tailor János Libényi attacked the monarch with a kitchen knife. The blade was diverted by the uniform’s stiff collar and left a cut in the emperor’s neck before Libényi was overpowered by O’Donnell and a brave citizen by the name of Joseph Ettenreich who happened to pass by the scene of the crime.

This close shave left Vienna and the imperial family in utter excitement. While the assassin was first tried and then executed a week after his heinous attempt on the emperor’s life, services were held to thank God for holding His hand over the youthful monarch. Since Franz Joseph was unmarried and had no children his brother Ferdinand Maximilian (born in 1832) would have succeeded him to the throne. Archduke Ferdinand Max immediately called upon the good people of Vienna for donations to build a church as a votive offering for the survival of the emperor. The remarkable act of brotherly love and Christian devotion met with an enormous response; funds were solicited from throughout the empire. The construction of the Votive Church on the Ringstraße (still a major tourist attraction in Vienna) began in 1856; the church was consecrated on 24 April 1879 on the occasion of Franz Joseph’s and Empress Elisabeth’s silver anniversary.

Five years after the gruesome attack on the emperor’s life Ferdinand Maximilian’s place in the line of succession was taken by Franz Joseph’s son Rudolf (1858-89). The fact that Archduke Max remained second in line and that the heir to the throne was a vulnerable child should become a bone of contention for the two brothers soon enough.

Ferdinand Maximilian was well educated, a sailor prince trained in the Austrian navy, adventurous, clever and ambitious. Unfortunately his position within the family did not provide him with anything useful to do apart from travelling. His position was that of inspector general of the navy – a high rank, but certainly not a central one. It did not improve the relationship with his elder brother that Max was also charming and approachable and a popular public figure, quite different from the aloof and self-contained emperor. In 1857 Ferdinand Max was appointed governor-general of Lombardy-Venetia. Two years later the emperor dismissed his younger brother from this position because he considered Max’s policies too liberal. When Austria lost most of its Italian possessions after the war of 1859, the frustrated archduke retired to Trieste where he built Miramare Castle and spent his days reading, collecting, writing poems and dreaming of a task suitable for his talent and position.

The prospect of being a crowned monarch, for example, instead of a mere archduke was music to his ears. Early in 1863 Ferdinand Maximilian was offered the throne of Greece, after King Otto I had been expelled from the country. Even Queen Victoria supported his candidacy, and she was usually hard to win over. However, Max refused. Apart from the fact that neither he nor his wife Charlotte, a Belgian Princess he had married in 1857, really wanted to go to Greece, Max stated that he would never accept a crown that had already been offered unsuccessfully to half a dozen other princes.

Another reason for passing up on the Greek throne was that there still remained bigger fish to fry. This is not the place to dwell on the French intervention in Mexico; yet since he first came up with the idea of reviving the Mexican Empire in 1861, Emperor Napoleon III had favoured Ferdinand Maximilian for the top job: the catholic archduke with his liberal and educated reputation, a dashing and daring personality, seemed perfectly capable (with a little help from French armed forces) of guaranteeing peace and order in a country wracked by civil war, poverty and social inequality. On 3 October 1863, after three years of uncertainty, mostly caused by French military setbacks against Benito Juarez’s republican armed forces, Ferdinand Maximilian received a delegation of Mexican conservatives at Miramare. They opposed President Juarez and formally offered him the imperial crown of their nation. In his answer, Maximilian stressed his determination to have the Mexican people asked what kind of government they wanted for themselves – he would not become ruler unless the vote for an empire was ratified by the Mexican nation.

Cesare dell’Acqua, Maximilian receiving the Mexican Delegation at Miramare (1867), Historical Museum of Castello di Miramare

Both Archduke Ferdinand Max and his beautiful and ambitious wife Charlotte then became smitten with the Mexican idea. While the couple studied the history, resources and geography of their chosen nation and took lessons in Spanish with an optimism that was fuelled by the enthusiastic and supportive French court, other crowned heads remained sceptical. In March 1864 Queen Victoria noted in her diary that she could not understand why Ferdinand and Charlotte were going to Mexico. The future of this nation did not seem promising for such an undertaking, judged on the base of historical fate and political circumstance: The First Mexican empire had only lasted two years (1821-3) and ended with the execution of Emperor Iturbide. 40 years later the Monroe doctrine would surely forbid the United States to accept a power on its borders which represented an interest imported from Europe. And had the Mexican delegation not been too confident in suggesting that the empire would be welcome throughout the country and that there was no imminent threat from the republican supporters of President Juarez?

It seems remarkable that Emperor Franz Joseph refrained from influencing his younger brother’s decision. He made it very clear that the imperial adventure would be his brother’s decision alone and would be kept separate from Austrian interests: In Nancy Nichols Barker’s words Franz Joseph ‘refused to guarantee the new empire, refused to guarantee a loan, refused to send a member of the Austrian cabinet to the offer of the crown, and even refused to permit the use of his name in the speech of acceptance.’[i]

However, Franz Joseph neither pushed Max and Charlotte into accepting the Mexican Crown, nor did he try to dissuade them. His biographer Jean-Paul Bled assumes that Franz Joseph ‘may have welcomed an ideal way of ridding himself of a brother who had perhaps become an embarrassment’.[ii] Maybe he also appeared to be a rival. Following the Austrian defeat at Sadowa there had been calls for the emperor’s abdication and his replacement with the popular Ferdinand Max (since the archduke had not been involved in the war he was quite naturally popular with the masses). Franz Joseph might have thought of his younger brother as a prince close to the throne and ambitious enough to claim power one day.

Of course getting rid of a brother has to be understood in exclusively dynastic terms here. Astonishingly enough, the question of succession to the Austrian throne only came up officially when Ferdinand Maximilian and Charlotte had long made it public that they would be delighted to accept the Mexican Crown. When they went to Vienna on 19 March 1864, they were presented by the Austrian Foreign Minister Count Rechberg with a ‘family pact’ stating that Maximilian and all his descendants would resign their succession rights in Austria. What is more, Maximilian would lose his civil list and his rights as archduke – this also included the privilege to be regent in case young Rudolf would lose his father while still being a minor.

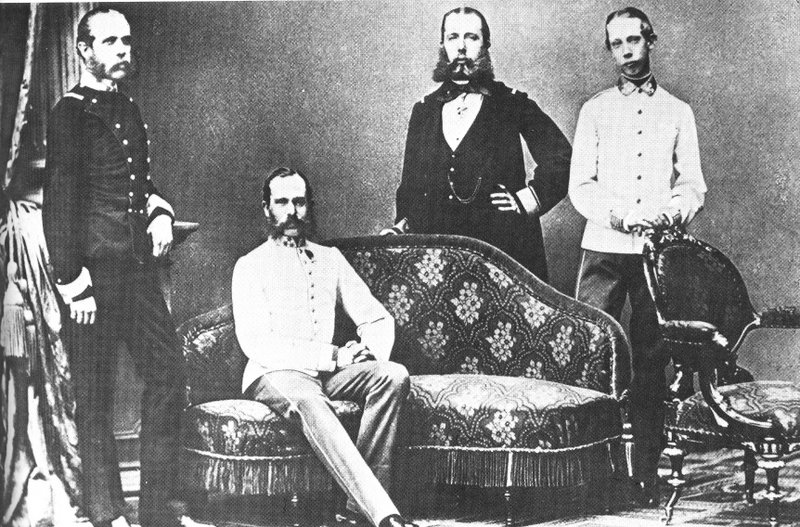

Ludwig Angerer, Habsburg family photo showing (from left to right) Archduke Karl Ludwig, Emperor Franz Joseph (sitting), Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian, Archduke Ludwig Viktor (around 1863)

Ever since the preliminary negotiations in 1861Ferdinand Maximilian had been aware that giving up his place in the line of succession to the Austrian throne would be inevitable. Apparently he and the emperor then both had avoided to talk dynastic politics until it was high time. Max was appalled to learn he would have to give up far more than just his right to succeed; the loss of his private fortune, for example, even if he had to leave Mexico, affected him badly. Consequently he refused to sign the document.

Franz Joseph, as chief of the House of Habsburg, informed him that in this case he would refuse to authorize Maximilian’s acceptance of the Mexican Crown. The archduke, deeply hurt and upset, believed the whole affair had been deliberately set in motion by Franz Joseph behind his back and at the very last minute in order to force the issue. It would be hard to withdraw from the Mexican venture at this stage of the planning, with the international press, countless diplomats, Napoleon III and the Mexican delegation keenly watching and the general high esteem for the Habsburg prince at stake. King Leopold I of the Belgians admonished his daughter not to give way and to hold on firmly to Maximilian’s birth right (as well as to the fortune of the Habsburgs). The archduke himself was ready to let go the dream of the imperial throne if he could just keep what he believed was rightly his. On 27 March he informed the Mexican delegation in Trieste that he would retire his candidacy to the Mexican throne.

Informed of this decision, the impatient Napoleon III firmly put his foot down. Maximilian received a stern telegram stating that at this point of the planning a refusal was impossible and that the archduke was under the obligation to go all the way to Mexico – this being a matter of honour of the House of Habsburg. Moreover, financial and military agreements had been signed between Napoleon and Maximilian from which the latter could not withdraw without damaging Austro-French relations.

At the same time Franz Joseph grudgingly clarified that the family pact should be seen merely as a means to keep the Austrian throne safe from harm. The marriage of Ferdinand Maximilian and Charlotte had not yet produced any offspring, but the emperor thought it best to prevent any future Mexican descendant of the archduke from hoping to succeed to the Austrian throne. The door was at least slightly open for further negotiations. Franz Joseph confirmed an earlier arrangement between the two brothers that Maximilian would be granted one hundred and fifty thousand florins annually and that a contingent of Austrian volunteers would be recruited for Mexico. He could not be moved, though, to grant his younger brother a restitution of his rights to the Austrian throne should the Mexican enterprise fail.

On 9 April 1864 the emperor personally went to Miramare to convince Maximilian to sign the family pact. He was accompanied by an escort consisting of their brothers, the archdukes Karl Ludwig and Ludwig Viktor, as well as an impressive line-up of imperial ministers, chancellors and even more agnates. Franz Joseph and Ferdinand Maximilian locked themselves up in the library and obviously talked for hours; both were all churned up afterwards. Ferdinand Maximilian signed the family pact. The next day, Maximilian received the Mexican delegation and declared his acceptance of the crown, once more announcing that he intended to establish a constitutional monarchy in Mexico. Four days later, on board the Austrian ship Novara, he and Charlotte left Trieste for good.

This was not the last to be heard of the forced agreement between the Emperors of Austria and Mexico. Maximilian still felt badly cheated on and made sure this would be noticed in Europe. When Franz Joseph opened the parliamentary session of the Reichsrat with a speech from the throne on 14 November 1864, he only very briefly announced the family pact. The correspondent of the London Times noted four days later that the emperor ‘read that part of his speech in which the Emperor of Mexico is referred to very quickly, and a certain something in his intonation induced me to fancy that the subject was not to his taste.’ The ‘often mentioned compact’ was read in the Reichsrat, and the Times, among others, published a translation of its articles.

Now that the family pact was suddenly in the limelight and a document of political and public discussion, Maximilian reacted with a harsh protest letter that he sent to the Austrian court in 1865: ‘It is hardly believable’, he fumed, ‘that a family pact could become a matter of an official communication, presented to be discussed in parliament, without the initial consent of the two Emperors. Nevertheless we can assure you that the Emperor of Mexico was not consulted. Without a doubt it would have been more prudent had the Emperor of Austria covered all details related to a convention forced upon his brother in a supreme moment with an opaque veil.’ He further stated that it was only because of Franz Joseph’s initiative that he had agreed to accept the Mexican throne (which was definitely not true) and that he had been forced to sign a paper which his lawyers and he himself considered null and void. He also attacked Franz Joseph for the involvement of the Reichsrat which Maximilian considered ‘only competent to negotiate questions of succession which modify an act of the Pragmatic Sanction, and this only when they are summoned directly for this cause and in accordance with the princes’ interest, who, in this case, have not even been consulted.’ Here Maximilian clearly missed the point. The agnates of the House of Habsburg had been present as witnesses at Miramare when he signed the document; they can hardly be considered not informed. Maybe it was hard for the Emperor of Mexico to accept that neither his brothers nor any other members of the dynasty had protested against how Maximilian had been deprived of his position in the family pact.

Maximilian’s empire was not to last; it ended with his execution on 19 June 1867, only three years after he had laid the foundations for a second imperial rule in Mexico. The reasons are manifold, but unsettled matters of succession clearly contributed to its downfall. The emperor and empress did not have children to secure their newly founded nucleus of a dynasty. The forced adoption of the grandson of Emperor Iturbide in 1864 turned out to be a fatal idea, linking the historical failure of the first imperial enterprise to the second one. Moreover, it created, from the start, the impression that the Habsburg dynasty would not be willing or able to produce a line of succession alone.

The whole tragic affair of Maximilian’s death by Benito Juarez’s firing squad on Campanas Hill has naturally attracted much more attention than the somewhat dusty family pact of 1864. Yet it can be stated that the unsettled question of succession and of the former archduke’s position within the Habsburg dynasty still mattered when Maximilian lost his tottering throne and was finally executed. Apparently Juarez’s envoy in Washington, Romero, had justified arresting the emperor and his trial on the ground that Maximilian ‘had resigned his right as an Austrian Prince and would always remain a Pretender to the Mexican throne’ (The Times, 2 July 1867). After that an imperial family council in Vienna, the correspondent explained, had discussed to restore to Maximilian ‘all the rights as an Austrian Archduke which he had abdicated on ascending the Mexican throne on condition that he should renounce his pretensions as Emperor of Mexico’. As so often, too little was done too late.

The question of the Austrian succession thus mattered for several reasons: First, the Mexican politicians pondering the future of their state were very much aware that it mattered to them, if not now, then later. Second, it seems none of the European powers actually made a straightforward attempt to save Maximilian’s life; this might very well have been subtly influenced by the fact that he was not considered an agnate of the House of Habsburg anymore. And – to make it three – what about the possible effect the renunciation of his rights and position within the family had on Ferdinand Maximilian? The novelist Fernando del Paso uses artistic licence to describe the former archduke of Austria and count of Habsburg as an uprooted personality, troubled by the loss of status even though he just won a glittering crown. To some respect we can imagine Maximilian as legally and maybe also emotionally deprived of his place within his family and at the same time unable to establish a new dynastic position. With the emperor trapped in dynastic no-man’s-land, no ruler or government within the widespread European monarchical family actually felt responsible, neither for Maximilian’s life in Mexico, even less for his death.

Suggested Reading

Nancy Nichols Baker (1963), ‘France, Austria, and the Mexican Venture, 1861-1864’, French Historical Studies 3/2, 224-45.

Jean-Paul Bled (1992), Franz Joseph, Oxford and Cambridge / Mass.

Egon Caesar Count Corti (1928), Maximilian and Charlotte of Mexico, translated from the German by Catherine Alison Phillips, vol. 1, London, 332-60.

Paul Goulot (1906), L’expédition du Mexique (1861-1867) d’après les documents et souvenirs de Ernest Louet, vol. 2, nouvelle édition, Paris. Maximilian’s letter of protest can be found on pages 12-15.

Walter Hansen (ed.) (1978), Das Attentat auf Se. Majestät Kaiser Franz Josef I. am 18. Februar 1853. Vollständige und authentische Schilderung des entsetzlichen Ereignisses und der darüber gepflogenen Untersuchungen … First edition Vienna 1853, Pfaffenhofen.

Richard O’Connor (1971), The Cactus Throne. The tragedy of Maximilian and Carlotta, London, 100-105.

Fernando del Paso (2009), News from the Empire, translation by Alfonso Gonzalez and Stella T. Clark, London, 201-17.