The Prussian Duke of Sparta

Miriam Schneider

Dimitrios Vikelas (1835-1908), a prominent member of the Greek merchant diaspora in London and Paris, is now most famous as first president of the IOC, but was an acclaimed author in the nineteenth century. In December 1889 he published an article in the French paper “Revue des Etudes Grecques”. It formed part of a wider series of regular “Greek correspondences”, in which Vikelas informed the educated French public about political and economic developments in his small homeland Greece. This particular issue took its readers back to the last few days of the month of October and it portrayed the city of Athens in a state of festive emergency.

Dimitrios Vikelas, a shrewd observer of affairs in Greece. He was also the first Greek to be awarded a honorary doctor-rate by the University of St Andrews

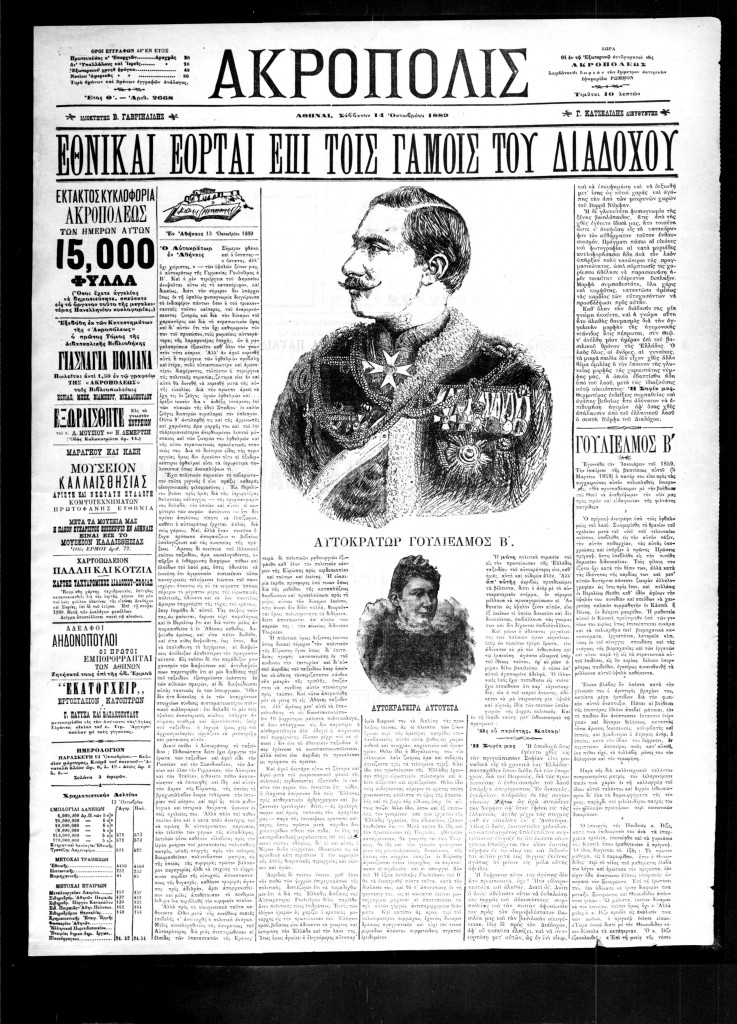

Every day, the cannons from the port of Piraeus announced the arrival of yet another highborn guest (the King and Queen of Denmark, the Russian Tsarevich, the Prince and Princess of Wales, the German Imperial couple…). Since this unprecedented crowd of crowned heads exceeded the capacities of the small and ugly royal palace, half a dozen of Athens’ most charming private villas had been ‘confiscated’ for the purpose of accommodating them. For ordinary mortals, it was virtually impossible to find lodgings, all hotels being fully booked and every family hosting relations from the provinces or from abroad. The population of Athens (appr. 115.000 souls) had almost doubled in size and Vikelas felt reminded of Paris during the Exhibition.

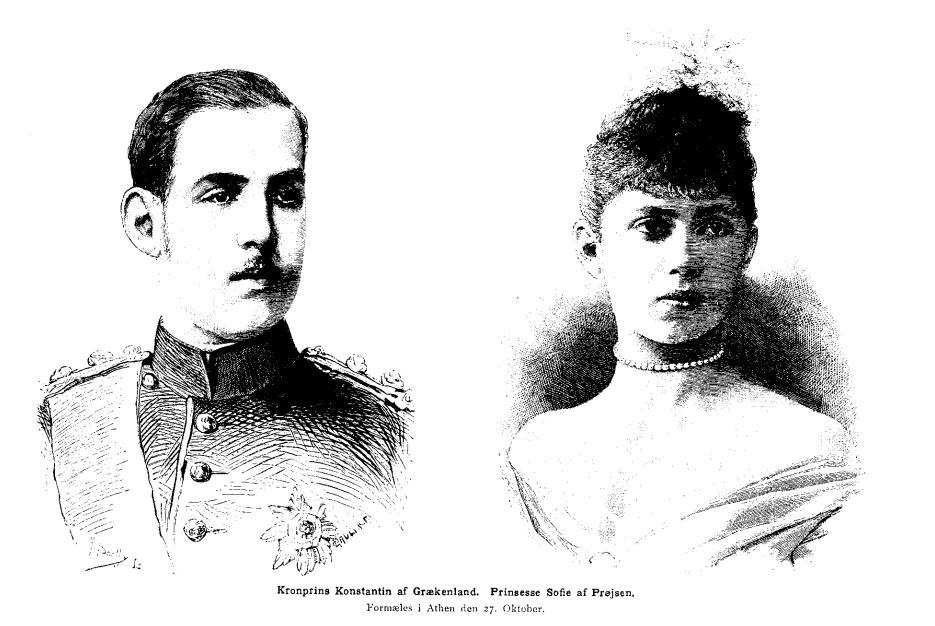

The event that was causing all this excitement was the wedding of Crown Prince Constantine (1868-1923), firstborn son of King George I of the Hellenes, and Princess Sophie of Prussia (1870-1932), the younger sister of German Emperor William II. Both as a dynastic family event and as a national occasion, it was an unprecedented affair. On the one hand, it broke with the notoriously anti-Prussian marriage tradition of the Danish Glücksborg dynasty, of which the Greek royal house formed a cadet branch. The young Duke of Sparta (as he was officially known) had already received a remarkably German education, and his choice of bride put the final seal on the Prussian outlook that would henceforth guide his policies.

On the other hand, the marriage was regarded as an historic event by the Greek nation, not only because it was the first royal wedding to take place in Athens in the young history of modern Greece, but also because some very specific hopes were attached to the alliance with Imperial Germany: Having placed great importance on dynastic relations ever since the creation of the Greek state, the Greeks were now hoping for a boost of their aspirations for unity with the island of Crete. In Vikelas’ words, an unusual explosion of joy broke through the general coldness that characterized the attitude of the Greek people towards the monarchy when the procession with the freshly married couple moved through the streets.

Constantine & Sophie in the Danish paper “Illustreret Tidende”, 20 October 1889 (Kongelige Bibliotek)

Crown Prince Constantine had always been at the centre of emotional attention in unruly Athens. And he would come to polarize his nation like no other member of his dynasty. This essay examines his troublesome relationship with the Greek people by viewing it through the prism of his Prussian education and marriage. The uncommonly high hopes that his small and aspiring nation attached to dynastic alliances would be disappointed by the logics of Balkan power relations. But the Prussian education and inclinations of the Duke of Sparta would, nevertheless, eventually backlash on politics in the so-called “national schism”.

The first native of the Greek Glücksborgs

Constantine had been heir to the throne from the day of his birth on 21 July / 2 August 1868. He was the firstborn child of King George of the Hellenes, formerly Prince William of Denmark. This fortunate though hardly enviable princeling had been selected by the great powers to succeed the deposed King Otto I in 1863. By producing a son only one year after their wedding, Constantine’s parents had broken the spell that had lain over the reign of their childless predecessors and secured for themselves the most reliable pledge of monarchical stability: a “native dynasty”. As Vikelas observed, Constantine was destined to be the first truly national King of Greece, “Greek by birth, religion, and education”[i].

Without precedent, the young Prince became a pioneer in virtually everything that happened to him, be it matters of education, ceremonial, or constitutional law. And he ignited the flammable passions of the Greek citizens, a highly political people enjoying one of the most radically democratic constitutions of the age. Only days after his birth, a first heated debate was raging in the Greek parliament regarding the title of the prince. Noble titles had been abolished by the constitution, but the King and his willing prime minister were able to circumvent the law, and Constantine would henceforth be officially known as “Duke of Sparta”, although the Greek people preferred to call him “Diadochos” (heir to the throne). His age of majority, his civil list, and his military posts would be further topics of debate. But Constantine was also an object of high hopes and affection. His rites of passage in particular became highlights of enthusiasm among an otherwise reluctantly sympathetic public. The declaration of his majority in 1886 was celebrated as a national occasion attended by the entirety of official Athens, by all the municipal mayors of the Kingdom and by deputations from all the Greek communities abroad. Its splendour was only surpassed by his marriage festivities three years later.

Falling in love with/in Prussia

Constantine was hailed as a Greek native and, therefore, great care was taken to provide him with as nationalized an education as possible. He was raised in the Orthodox faith. And his tutors included some of the most prominent professors of the young University of Athens. The most famous amongst them was Konstantinos Paparrigopoulos (1815-91), the founder of Modern Greek history and one of the spiritual fathers of the “Great Idea” (Megali Idea) of Greek territorial expansion and neo-Byzantine revival.

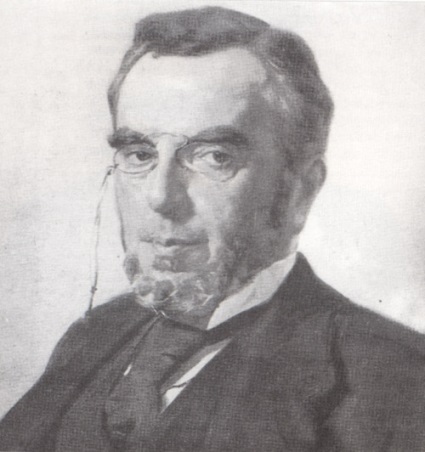

Strangely enough, though, the office of governor to the Diadochos was occupied by a German philologist. Dr. Otto Lüders (1844-1912), a Catholic from Prussian Westphalia, had previously been attached to the German legation as an archaeological adviser. In 1877, he became the strict but much-loved teacher of the Greek royal princes, probably as a result of his marriage to a prominent Greek lady. He would remain governor to the Diadochos for nine years and, when the Prince came of age, become his lord chamberlain.

German teachers enjoyed a good reputation in nineteenth-century royal Europe. But Lüders was still an unlikely choice. For the members of the Glücksborg royal family were renowned for their collective mistrust of everything Prusso-German, which they maintained ever since the bitter defeat of the Danish army in 1864. There was a veritable conspiracy theory going around official Europe in the 1870s-1900s according to which the King’s sisters, Alexandra Princess of Wales and Empress Marie of Russia, were trying their utmost to influence their countries’ policies against Germany. King George himself was certainly more moderate in his behaviour; but he was still known for his Francophile attitudes and in 1895, Greece was the only European power not to send a squadron to the opening of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Canal. This was done expressly in order to signal disapproval of a potential threat to Danish naval interests.

The Greeks, moreover, were a people suspicious of foreign influence ever since the debacle of the reign of the Bavarian King Otto. Lüders’ position thus became increasingly undermined by Greek courtiers who resented the influence of the foreigner, objected to his openly Prussian sentiments (he refused to wear Greek uniform or to adopt the Greek citizenship), and feared that other powers might take offence.

In 1889, the year of the Greco-Prussian marriage, Lüders’ opponents finally succeeded and he was dismissed. But by then, the ‘damage’ had already been done. As if in expression of gratitude for successfully brainwashing the Greek Diadochos, the German government offered the disgraced official a consular career.

During the prince’s most formative years of his youth and adolescence, Lüders had imparted to his pupil an indelible predilection for everything Prussian. As a natural consequence of his education, Constantine had gone and continued his studies in Germany, spending three semesters at the universities of Leipzig and Heidelberg, and, much against the intentions of his Francophile father and Russian mother, also completing his military training in the German Imperial Guard. Both the Greek land and sea forces needed reorganization and the necessary know-how was sought from relevant powers, but while the King’s second son joined the Danish naval cadet academy, Constantine’s was a more ambivalent choice.

In addition to his internalising of Prussian military values, Constantine’s sojourn in Germany also had the lasting effect that, while staying with the Imperial family in Berlin, he fell in love with the second to last daughter of the ill-fated Emperor Frederick III. As a child of the English-born Empress Frederick, Princess Sophie was not a bad choice. But as the younger sister of the soon-to-be Emperor William II she brought Constantine into opposition with everything that his dynasty stood for. His mother, Queen Olga, was rumoured to be so upset by his choice of a Protestant, German princess that she even considered boycotting the wedding. The Greek people, however, were enthused.

An auspicious marriage

There were certainly no hidden agendas behind Constantine’s spontaneous love affair. But as soon as the rumours were confirmed in September 1888, Greek society was alive with hope for material gains from the alliance. It was regarded as an auspicious match since, by some curious twist of fate, Constantine had happened to gain a bride named Sophie. According to an ancient legend, the Byzantine Empire would be resurrected again when a King named Constantine and a Queen named Sophia would ascend the Greek throne, bringing back forever into Greece’s fold the city of Constantinople and the Hagia Sophia. “Oh, how the hearts of all the Greeks beat / when we pronounce SOPHIA, CONSTANTINE! / We believe that you are heaven-sent / to liberate a people long enslaved”, wrote even one of the most satirical papers of the age, Neos Aristophanis.[ii]

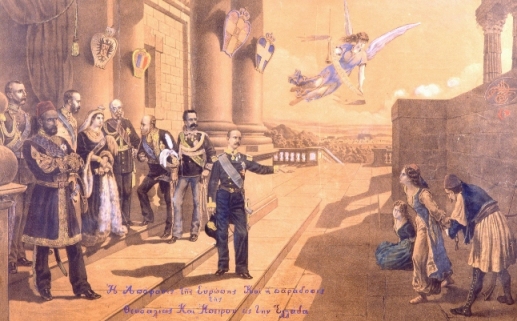

A graphic depiction of the cession of Thessaly and South Epirus to Greece. Help from the monarchical concert of Europe was also what Greeks hoped for in 1889 (National Historical Museum, Athens)

Superstition combined with ideology, since the hope for the recovery of Constantinople formed part of the “Megali Idea” that inspired Greek foreign politics for much of the period from the 1880s to the 1920s. Ever since the formation of the Greek nation state in 1830, Greece had been struggling to achieve unity with all the Greek-populated territories still under Ottoman rule. In 1863 King George had brought with him an English dowry: the Ionian Islands. Following the Eastern Crisis of 1875-78 he had managed to acquire Thessaly and South Epirus. But, next to Macedonia, the island of Crete remained one of the most symbolic bones of contention. The island was plagued by regular outbursts of unrest, one of which formed the immediate backdrop to the Greco-Prussian marriage of 1889. When Sophie and Constantine drove through the streets of Athens, Vikelas remarked, refugees who had fled from a state of martial law in Crete were mingling with the crowds reminding Athenian citizens of the fate of their unfortunate fellow-Greeks. In this context, the ancient prophecy was interpreted to mean the very tangible support the Glücksborgs might obtain in their quest for unity with Crete from their new highborn relative, the mighty Hohenzollern Emperor.

As foreign diplomats observed, the presence of all the highborn wedding guests in the capital city flattered Greek “national vanity”, and Athens’ countless newspapers published lengthy portraits of all of them. Particular attention was paid to Emperor William II, who, as the ruler of Europe’s greatest continental power, was expected to work wonders. “My dear brother-in-law”, he was even reported to have said to Crown Prince Constantine after leaving the Metropolitan Cathedral, “I offer you Crete – take it!”[iii] The Greeks, remarked French journalist Gaston Deschamps, were always courting mighty men which they hoped might favour their aspirations, and they were always disappointed.

A troublesome relationship

When Dimitrios Vikelas wrote his report in December 1889, he already knew that nothing had come of the hopes attached to the Greco-Prussian marriage. The Greek government and royal family had never even wished for a political alliance. And in Germany, there had been no intention of any such offer. One month before the wedding, Chancellor Bismarck had expressly told his sovereign that the dynastic match between the two royal houses must never even appear to have the slightest political consequence. Considering Germany’s interest in good relations with Turkey and the Greek tendency to be on a collision course with almost every European power, even the merest hint of a mutual understanding had to be avoided. The Emperor’s visit to Athens was, thus, immediately followed by a call on the Sultan to strengthen economic ties with Constantinople, a step which, to the hopeful Greek public, felt like a slap in the face. Willingly accepted disappointment would continue to characterize the troublesome relationship that Germany shared with Greece.

Personal relations between Emperor William and the crown princely couple deteriorated when, in 1891, Princess Sophie decided to snub her ostentatiously Protestant brother by adopting the Greek Orthodox faith. She had to expect little sympathy when Greece, in 1897, lost a rash and disastrous war over Crete to the Ottoman Empire’s German-trained forces. While Sophie begged for help via her family channels, William would have remained merciless if Russia and Britain had not intervened. He also opposed the candidature of Constantine’s younger brother, Prince George, as high commissioner of Crete, which, following the unhappy performance of the Diadochos as commander in war, constituted the dynasty’s last, futile chance to effect the cession of the island.

William’s policies only changed when Greece emerged as a more helpful ally in Germany’s drive for the Near East. Regarding his brother-in-law as an ideal link with a growing military power in the Mediterranean, the Kaiser was more than obliging when, in 1903, a number of Greek officers selected by the Duke of Sparta (among them the future General Metaxas!) were sent to the Berlin War Academy to learn from the teachers of their enemies. These officers would come to comprise the Crown Prince’s “little court”, which, in opposition to King George’s Francophile policies, increasingly advocated a German-style reorganization of the Greek army.

Unfortunately, Constantine’s popularity reached an all-time-low in the years 1897-1909, due to the disaster of the Greco-Turkish war and to his alleged favouritism. In 1909, a military coup even forced him and all the Greek princes to temporarily resign from their military offices. It brought Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936) to power, the liberal politician who, through one last revolt, had achieved what had eluded the Glücksborgs – the cession of Crete. In a strange reversal of fate, the crown princely couple, personae non gratae in Athens, were welcomed to spend a short term of exile in Germany, their eldest son George (the future King George II!) even being allowed to enrol in the Imperial Guard.

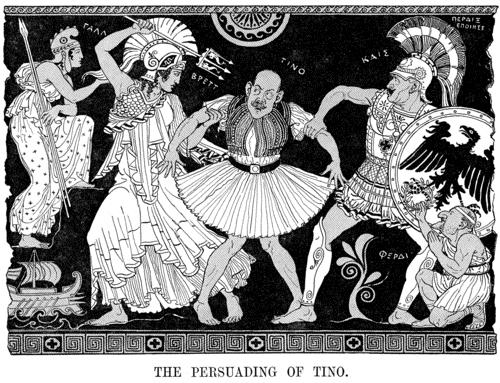

Punch, 24 November 1915: A relief representing (from left to right) France, Great Britain, King Constantine (“Tino”), Emperor William II, Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria

The Greek government would eventually invite a French military and a British naval mission to reorganize their forces, but Constantine would never forget the support he had received from the German Emperor in 1903 and 1909. When, only months after his succession to the throne in 1913, he paid a state visit to Berlin, he gave a speech in which he ascribed the Greek military successes of the first Balkan War almost exclusively to German help.[iv] It caused a veritable scandal in Greece and France and presaged what would follow in the years 1914-1917, when a major “national schism” evolved between the King and his Prime Minister Venizelos over the question of whether to enter the First World War.

As we know, Constantine and his war-weary conservative supporters refused for years to give up neutrality, while his liberal government favoured the Allied cause. One could argue that the parameters that shaped his first short reign – his decision not to enter into war with Germany – had taken their most momentous beginnings in his Prussian education and marriage.

Further Reading

This essay is based on documents held by the Polit. Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes, Berlin, and the National Archives, Kew. All Greek newspaper clippings are from the Library of the Hellenic Parliament.

- Christmas, Walter, King George of Greece (London, 1914).

- Deschamps, Gaston, La Grèce d’aujourd’hui (Paris, 1894).

- Hering, Gunnar, Die Politischen Parteien in Griechenland, 1821-1936 (Munich, 1992).

- Joachim, Joachim G., Ioannis Metaxas: The Formative Years, 1871-1922 (Mannheim et al., 2009)

- Kiste, John Van Der, Kings of the Hellenes: The Greek Kings, 1863-1974 (Stroud, 1994).

- Koliopoulos, John S., and Thanos Veremis, Modern Greece: A History since 1821 (Malden, MA, 2009).

- Morbach, Andreas, Dimítrios Vikélas, patriotischer Literat und Kosmopolit: Leben und Wirken des ersten Präsidenten des Internationalen Olympischen Komitees (Würzburg, 1998).

- Olden-Jørgensen, Sebastian, Prinsessen og det hele Kongerige: Christian IX og det Glücksborgske Kongehus (Copenhagen, 2003).

- Pelt, Mogens, ‘Organized Violence in the Service of Nation-Building’, in Ottomans Into Europeans: State and Institution-Building in South Eastern Europe, ed. by Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Wim P. Van Meurs (London, 2010), 221–44.

- Polykratis, Iakovos Th., ‘Konstantinos’, in: Neoteron enkyklopaidikon lexikon, ed. by Ioannis D. Passas (Athens, 1948), XI, 873-77.

- Vikelas, Dimitrios, ‘Correspondance Greque’, Revue des Etudes Grecques, vol. 2, 1889 (26th December), 428-32.

- Vikelas, Dimitrios, ‘Vingt-Cinq Années de Règne Constitutionnel en Grèce’, La Nouvelle Revue, 1889, 492–519.

[i] „son premier roi national, Grec de naissance, de religion et d’éducation” (Vikelas, Vingt-cinq années, p.505).

[ii] Ὠ! Πόσον πάλη ἡ καρδία ὃλων μας τῶν Ἐλλήνων / Καί μόνον σάν προφέρομεν ΣΟΦΙΑΝ, ΚΩΝΣΤΑΝΤΙΝΟΝ! / Ἀπό Θεοῦ πιστεύομεν ἐσᾶς ἀπεσταλμένους / Νά ἐλευθερώσετε λαούς πρό χρόνων σκλαβωμένους. Neos Aristophanis, 30 October 1888.

[iii] “Mon beau-frère, je vous offre la Crète, prenez-la!” (Deschamps).

[iv] “I do not hesitate to assert once more aloud and openly that, next to the invincible valour of my Greeks, our victories are due to the principles of war and the science of war, which I and my officers acquired here in Berlin with my dear Second Regiment of Foot Guards, at the Staff College and in intercourse with the Prussian General Staff.” Constantine I, 6 September 1913.