The Explorer Prince

Maria-Christina Marchi

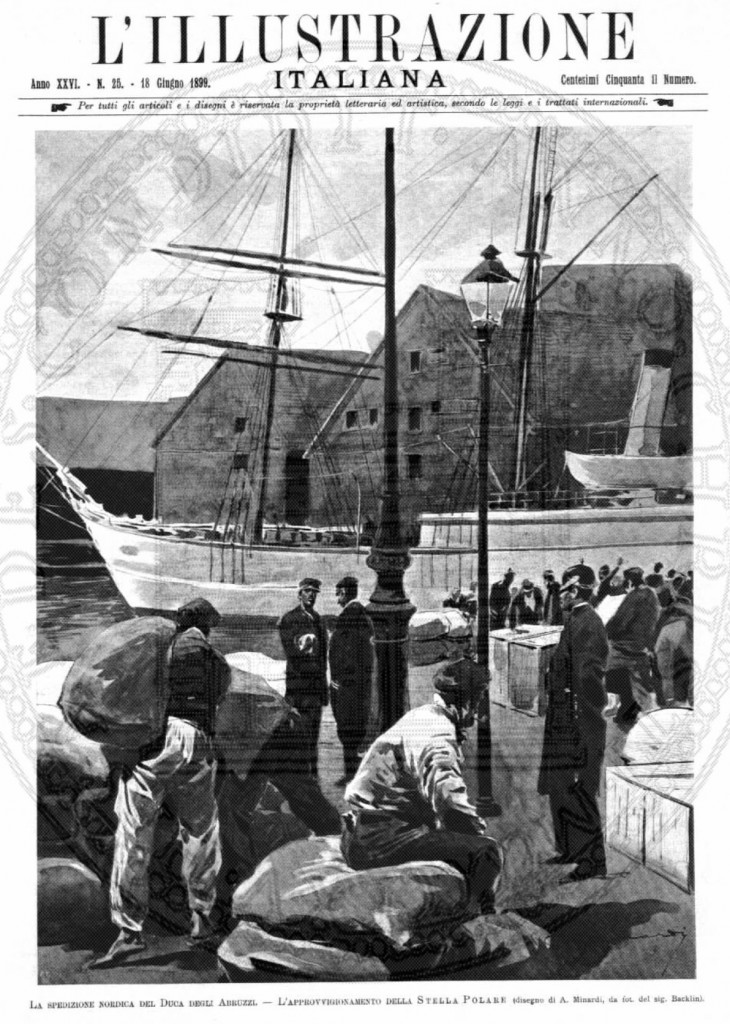

‘At eleven thirty on Monday, 12 June, greeted by the gunfire of the fortresses and of the ships, and cheered by the crowds, the Stella Polare (Polar Star), on which the young prince Luigi Amedeo of Savoia, Duke of the Abruzzi, lieutenant of the ship, was travelling, together with his companions set sail from Christiania towards the Pole, so as to better study the geography of the Franz Josef land. The ships in the harbour were decorated with flags; the sailors were shouting their hurrahs; it can be said that the entire population of Christiania had rushed to give a cordial, clamorous farewell to the Italian prince who responded […] to this enthusiastic reaction by waving his cap. […] The sea was calm; the sky was cloudy, but not menacing; everything seemed to wish the maritime and scientific endeavour […] well.

The Prince and Princess of Naples, who had arrived in Christiania on Saturday evening, so as to be able to bid their cousin farewell and bring him the greetings and well-wishes of the King and Queen, were also greeted by the crowd with repeated hurrahs.

King Oscar [of Sweden-Norway] himself gave the order that the fortresses saluted the departure of the Stella Polare with twenty-one cannon shots; all of the newspapers wished the travellers a happy journey… Rarely had there been a departure for a trip of Arctic exploration so fervently greeted by the royal institution, by the international navy in the port, by the population, by the press.

[…] Salve, o Principe! E sempre avanti Savoia!’

Illustrazione Italiana, Anno XXVI, N.25, 18 June 1899

The scene described in the Illustrazione Italiana narrated the departure of an expedition set out to reach, for the first time in history, the northern-most tip of the planet: the North Pole. However, it was no ordinary expedition, because at the helm of the Stella Polare stood no ordinary man, but a Prince of the House of Savoia, the Italian royal family. The ceremonial pomp surrounding the ship’s departure suggests that the expedition was important to both the royal family, since the heir to the throne was present in Christiania, and to the Italian people. This was made evident by the extensive press coverage of the occasion. At the centre of it all was Luigi Amedeo, who was only 26 years old at the time, and had already begun making a name for himself as both an explorer and mountaineer. He had voluntarily embarked on this mission to conquer the North Pole, in a bid to expand the scientific knowledge of its geography, while simultaneously promoting a positive image of the royal family. He served as a figure with which to promote the heroic and progress-driven nature of the Savoia family; he was their explorer Prince.

Luigi Amedeo Giuseppe Maria Ferdinando Francesco of Savoia was born on 29 January 1873, in Madrid, to Amedeo of Savoia (1845-1890) and his wife Maria Vittoria Dal Pozzo della Cisterna (1846-1876). His father, son of Vittorio Emanuele II and younger brother of Umberto I, was at the time the king of Spain, yet would have to flee the country and abdicate his throne shortly after Luigi Amedeo’s birth. Thus, Luigi Amedeo and his two older brothers grew up in Italy and were educated in their home country. At the tender age of six, after his mother’s premature death and according to Savoia military tradition, Luigi Amedeo was enrolled in the Royal Navy in Genoa as a ship’s boy and later moved to the Royal Naval Academy in Livorno, quickly rising through the ranks. The Duke’s career as a world traveller began in 1889, upon his promotion to mid-shipman. He was assigned to the Amerigo Vespucci, a wooden-hulled sailing ship, which took him around the world, crossing from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, and all the way back to Italy. Only a few years later, in 1893, as second in command of the gun-boat Volturno, he sailed to Italian Somaliland – the first of the House of Savoia to do so –, where there was news of a possible revolt against colonial rule. His position in the navy gave him the opportunity to travel extensively, exposing him to the world, while simultaneously presenting a Savoia prince to foreign nations and national press.

However, although the sea was inextricably tied to his career, he was also very passionate about mountains and mountaineering. A common leisure pursuit among the Savoia family members, mountaineering was also one of the preferred hobbies of both Vittorio Emanuele II and Queen Margherita. Luigi Amedeo’s career as a climber took him further however, than either of the two monarchs could ever have imagined. Even before his expedition to Africa, the young Duke had conquered a number of impressive summits, including Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc. In 1894 he climbed the Matterhorn’s most demanding route, the Zmutt ridge, which had only been pioneered in 1879 by the English mountaineer Albert Frederick Mummery, who accompanied the Duke on his climb five years later. In 1897 he was the first man to summit Mount St. Elias in Alaska, after numerous expeditions, including one funded by National Geographic in 1890, had failed to reach its peak. His exploit was celebrated both at home and abroad, fuelling much admiration for the prince. After his Alaskan feat, Luigi Amedeo went on to climb numerous other peaks, making and breaking records, from scaling sixteen of the nineteen peaks in the Ruwenzori range in Uganda, to reaching the highest ever recorded height of 7500m on the K2.

Thus, from a young age the Duke of the Abruzzi was a well-travelled explorer and mountaineer, with an interest in pushing natural boundaries and the expansion of scientific knowledge. However, because of his royal status, he was no ordinary explorer and his achievements were used as examples of national character. His adventures meant that he best embodied Italian values, such as courage, as well as the desire to further scientific progress, all while representing the dynasty. His feats allowed the public to equate the Savoia with a degree of heroism that was much needed during the fin de siècle period, when the monarchy had been at the heart of a banking scandal and had endured the humiliating defeat of Adua in their Ethiopian colony. His journeys provided an opportunity for supplying both escapism, by turning them into adventure books, and success. This became particularly evident in 1899-1900, when the young explorer embarked on his journey to become the first man to reach the North Pole.

Unlike his previous journeys, Luigi Amedeo’s trip to the Arctic attracted widespread media attention. He had assembled a team of experts and close friends in an attempt to reach the top of the world – something that had never been achieved before. His team comprised his loyal second in command Umberto Cagni (1863-1932), Lieutenant Francesco Querini (1867-1900), Dr Pietro Achille Cavalli Molinelli (1865-1958) and a number of academic experts, who would study the geographical conditions of the North Pole. Moreover they were greatly aided by the guidance of Norwegian Captain Eversen (1851-1937) and his team of sailors who were better acquainted with the maritime conditions. It was meant to be both a journey of scientific discovery, as well as one of human conquest. In the introduction to his written account of the expedition, which was also translated into English as On the “Polar Star” in the Arctic Sea (1903), the Duke wrote:

The practical use of Polar expeditions has often been discussed. If only the moral advantage to be derived from these expeditions be considered, I believe that it would suffice to compensate for the sacrifices they demand. As men who surmount difficulties in their daily struggle feel themselves strengthened for an encounter with still greater difficulties, so should also a nation feel itself still more encouraged and urged by the success won by its sons, to persevere in striving for its greatness and prosperity.

This message is important in understanding the underlying motives behind such a journey, such an expedition – and why the Italian crown would be so interested in financing it. The desire to draw attention to the success of the Italian royal family, which was directly linked to national success, was an important step in creating a positive image of Italy after a particularly difficult decade of political failures. Moreover, during the expedition Umberto I was assassinated and the wave of monarchical support that was triggered by the event was further fuelled by Luigi Amedeo’s role as national hero. Despite the expedition’s failure to reach the North Pole, they managed to go further north than anyone before them, reaching a latitude of 86°34’, and thus securing a symbolic victory. Not even the fact that the Duke had not been with the team who had reached the northernmost point due to injuries he had sustained during the voyage, detracted from this Italian success story.

The expedition was covered by the press from start to finish and the journey was followed by numerous news sources, making it a public event. The departure was widely reported on, and the Italian heir to the throne, the future Vittorio Emanuele III, as well as King Oscar II of Sweden were present at Christiania when the Duke of the Abruzzi’s vessel had set sail on June 12. The public’s enthusiasm for the voyage grew, and according to a contemporary commentator, upon the royal’s return in September 1900 he was greeted in Chiasso by ‘incessant applause’ and his carriages ‘struggled to make way to the Palazzo della Cisterna through the crowd, who gripped by a true frenzy, unusual for the people of Turin, called the Duke numerous times to the balcony.’[1]

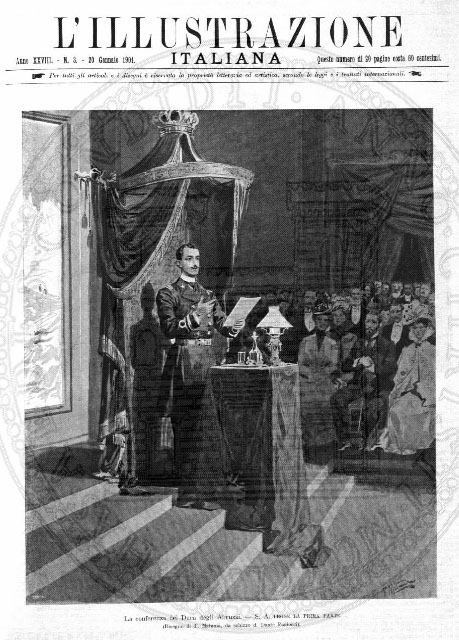

The expedition was followed by a conference in Rome in January 1901, which was held in order to present Luigi Amedeo’s findings. His efforts were described by the press as ‘heroic’ and that it had been a ‘triumph for the nation.’ The conference lasted four hours, during which the Duke discussed his findings and highlighted the accomplishments of the expedition. Count Alessandro Guiccioli (1843-1922) noted that the conference had been a success mainly due to the Duke’s powers of attraction, rather than the material handled, highlighting the importance of his royal status in procuring visibility for the crown and nation.

Duke of the Abruzzi speaking at the conference on the Stella Polare expedition, Illustrazione Italiana, 20 January 1901

The press and nobility were not the only ones to be attracted to this tale. The story of the journey was even of interest to Emilio Salgari (1862-1911), the renowned writer of pirate adventures, who was fascinated by the Duke’s adventures and managed to secure the details of the voyage before the newspapers, publishing his embellished account of the journey before Luigi Amedeo’s return to Italy. The “Polar Star” and its adventurous journey (1900) was so popular that a second edition was released that same year during the Christmas period. And it was not just Salgari who believed that the Duke’s achievement should be celebrated by the literary world, as well as by the scientific one.

Many professional and amateur poets wrote odes and sonnets about the Stella Polare, including Giovanni Pascoli (1855-1912), one of the most celebrated bards of the nineteenth century. Pascoli wrote one poem titled ‘To Umberto Cagni’, the expedition’s second in command, and the one ‘To the Duke of the Abruzzi and his Companions.’ In the latter the poet celebrated the young Savoia’s mission, calling him a ‘pilot of heroes’, celebrating his pioneering endeavours, as well as thanking him for ‘bringing us [Italians] victory.’ His stories went beyond the Italian borders as well, and in the early twentieth century, numerous books on the Duke’s polar expedition were published all over Europe, including in Great Britain, Germany and the Netherlands.

A collection of commemorative postcards, now held in the Archivio del Risorgimento di Bologna, was published between 1899 and 1901

The widespread interest in the adventure, its fairytale-like quality with the inclusion of a princely figure, attracted much public attention and helped build an image around the Duke that tied crown and nation together in the mastering of arduous challenges. He featured on the covers of illustrated magazines and children’s books alike, became a hero in the press and in literature, and allowed Italy to achieve new glories in the field of exploration. The Duke distracted from the wider, domestic problems and allowed the monarchical fairytale to continue for a little longer, gaining popularity for himself as well as for his dynasty. Although his chances of inheriting the crown were slim, he nonetheless served as an asset for the crown in his role as a young explorer prince.

During his youth the Duke served as a symbol of morality and heroism in Italy, and despite his disappointing performance during the First World War, he was remembered as an explorer and pioneer, and a ‘truly national hero.’[2] After his early death due to prostate cancer in 1933, Professor Giotto Dainelli (1878-1968), a geographer and fellow of the Accademia d’Italia, gave a paper commemorating the royal prince at the evening meeting of the Royal Geographical Society on 15 May 1933. In it he described the Duke of the Abruzzi as having a ‘moral significance which reaches beyond his glorious activity as an explorer; for he has been, to us, an example and a pure symbol, a forerunner and a prophet, in grey times, of the actual rebirth of our country.’

Images:

Stella Polare 1: The departure of the Stella Polare, Illustrazione Italiana, 18 June 1899 © BiASA

Duca degli Abruzzi: The Duke of the Abruzzi, La Tribuna Illustrata della Domenica, 21 May 1899

Stella Polare 3: Duke of the Abruzzi speaking at the conference on the Stella Polare expedition, Illustrazione Italiana, 20 January 1901 © BiASA

3 postcards commemorating the expedition, all printed between 1899 and 1901, from the Archivio del Risorgimento di Bologna

Further Reading:

Bridges, Peter, ‘A Prince of Climbers’, VQR, Vol.76, (2000), pp.38-51.

Dainelli, Giotto, ‘The Geographical Work of H. R. H. the Late Duke of the Abruzzi,

The Geographical Journal, Vol. 85, N.1, (Jul., 1933), pp.1-8

Savoia, Luigi Amedeo di, On the “Polar Star” in the Arctic Sea, (London: Hutchinson, 1903).

Tenderini, Mirella and Michael Shandick, The Duke of the Abruzzi: An Explorer’s Life, (Seattle: The Mountaineers, 1997).