The Politics of a Royal Marriage

Charles A. M. Jones

Imagine, if you will, a plush drawing room brightly lit by the summer sun. Prominent in this room there is a large vase, richly gilded, with an emblazoned portrait of a King long deceased. Upon closer inspection, one will notice that the weight of this priceless object has caused great strain upon the delicate pedestal. Several prominent cracks appear at its base, ultimately threatening the longevity of the piece. This objet d’art can also stand as a metaphor for the Anglo-German dynastic network and its inability to stem the growing tide of nationalist rivalry. The following is much less a narrative of this vase’s destruction, but more an examination of one of the first cracks to manifest itself – the union of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863.

The royal marriage itself, though not the metaphorical crack, can be seen, as the catalyst that first brought simmering tensions out of the political and directly into the personal family sphere. The root of the hostility stemmed from a disagreement between the German Confederation (led by the kingdom of Prussia) and the Kingdom of Denmark over the governance of two duchies, Schleswig and Holstein. The situation had already caused a war between the two powers (First Schleswig War 1848-51) that resulted in a Danish victory and the London Protocol of 1852. As a result, the Duchies became separate entities under the control of King Frederick VII of Denmark. The matter remained far from settled, however, due to Frederick’s childless state. The main political question became whether Frederick’s chosen heir, Prince Christian of Denmark, or the German candidate, Frederik August of Augustenborg, should succeed as Duke of Schleswig-Holstein.

In November of 1860, Albert Edward (Bertie) returned to Britain after a triumphant tour of Canada and the United States. The young prince, who had up to this point in his life been confined to the schoolroom, had metamorphosed from a shy boy into a charismatic and, to quote Queen Victoria, ‘very talkative’ young man. The tour had done wonders for the prince’s self-esteem and had liberated his spirit. To Prince Albert’s credit, considering his borderline draconian approach to Bertie’s education and training, he did not attempt to crush this new found sense of self completely. He even allowed his son to smoke at the age of 19. However, he did send Bertie back to finish his studies at Oxford before enrolling him at Cambridge University in the January 1861. Both Albert and Victoria felt that Bertie would need to be steadied, and what better way to curb a young royal stallion than to marry him off as soon as possible? The hunt for marriage prospects, though mainly for Bertie’s benefit, was also a distraction for the worried Victoria. The health of her mother, the Duchess of Kent, was in decline, and the Queen herself was already showing signs of the melancholy that would leave a lasting impact on the rest of the Victorian Era.

The qualifications for a suitable bride were, on the face of it, simple enough: 1) She should be a German, 2) a Protestant, or at least willing to convert, and 3) she had to have the character and demeanour befitting a future Queen of England. To assist them on the continent in this great undertaking, the royal couple turned to their daughter Victoria (Vicky), the Princess Royal. As the wife of the Crown Prince of Prussia (later Emperor Friedrich III) she was conveniently located in Germany. Vicky already had one matchmaking success under her belt, having arranged the engagement of her sister Alice and Prince Louis of Hesse. Dutifully, the princess worked her way through all the available brides that fit the parameters established. Though there were a few potential German candidates, Elisabeth of Wied coming the closest to being seriously considered, Vicky and her lady-in-waiting and confidante Walburga ‘Wally’ Paget found fault with all of them. In a letter to the Queen (20 April 1861) she complained that ‘I sit continually with the Gotha Almanack in my hands turning the leaves over in hopes to discover someone who has not come to light!’

Yet, there was one Princess who had been deferred from consideration: Princess Alexandra (Alix), the daughter of Prince Christian of Denmark. In previous correspondence, Vicky had mentioned Alix. Echoing the glowing reports she had heard about the young princess’ charm and beauty, she had even sent a photograph to Queen Victoria as early as December 1860. Vicky’s enthusiasm for the Danish beauty was clear and she thought her a perfect match for Bertie ‘though I as [a] Prussian cannot wish Bertie should ever marry her’. In the same letter she offered to have Wally gather further information, a task made easier by her husband’s position as British ambassador to Copenhagen. Though enthusiastic in her praise of Alix, Vicky was not unaware of the dangerous political ground she was treading on, that ‘an alliance with Denmark would be misfortune for us [Vicky and Fritz] here’. Her sentiments were shared in Victoria’s response to the photograph: ‘Princess Alexandra is indeed lovely! […] What a pity she is who she is!’ Albert’s response, according to Victoria, was surprisingly uncharacteristic considering his Anglo-German views. Upon seeing her photograph, he declared that ‘I would marry her at once’. More information about the ‘Danish beauty’ was requested and Wally was dutifully dispatched.

The later edition of Wally’s reports, collected under the strictest secrecy, only confirmed the praise surrounding the Princess. By February 1861, it was beyond question that Alix was indeed a perfect match for the Prince of Wales in many ways. Yet, she remained a politically and even personally unsuitable candidate. On one hand, the Schleswig-Holstein issue made her a politically explosive choice due to mutual Prusso-Danish animosity. Moreover, Victoria personally disapproved of the Danish royal house – a view likely based on Frederick VII’s allegedly dubious morality. With these red flags raised against her, Alix was placed in a bridal limbo of sorts. She was, however, mentioned more frequently in family correspondence, especially as the pool of German princesses dried up and parental concern over Bertie increased.

In the summer of 1861, Bertie was granted permission to go to Ireland for ten weeks of military training at the Curragh. While the Prince of Wales marched and drilled, Vicky, now Crown Princess of Prussia, set up a meeting with the “Danish Pearl” at Strelitz. Vicky’s opinion of the event is best captured in the letter she sent to her mother on 4 June 1861. ‘Oh if she only was not a Dane…I should say yes – she is the one a thousand times over.’ Alix’s “bewitching” charms, however, proved stronger than any anti-Danish prejudice held by Vicky or Fritz and it was finally agreed that Bertie and Alix should meet. The encounter at Speyer Cathedral on 24 September 1861 was a carefully arranged affair managed mainly by Vicky and Fritz, no detail left to chance. To avoid controversy, Bertie, who had been aware of the meeting’s significance, was officially in Germany to observe military manoeuvres at Coblenz. It appears that the only one left in the dark was Princess Alix. Though Bertie did appear to show some interest when he met the princess at Speyer, when questioned by Albert, he was adamant that he was too young and not ready for marriage. A plausible explanation for his hesitation did not take long to manifest itself.

Rumours, first circulating the barracks at the Curragh and later spread on the continent, eventually reached the attention of one Baron Stockmar, a trusted friend and longtime advisor to Prince Albert. In his letter to Albert (12 November 1861), he revealed that the Prince of Wales, during his military training in Ireland had begun an affair with a lady of easy virtues, Nellie Clifden. Albert, already suffering from his final illness, was completely devastated. Was it not bad enough that news about the possible union between Britain and Denmark had spread in the days following the meeting at Speyer? This prospect resulted in wounding letters, chiding him for even considering the possibility, from two men for whom he cared deeply, his brother Ernst (Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha) and even his devoted Stockmar. Now his eldest son, the heir to a throne whose reputation he had worked so hard to establish, had been ‘initiated in the sacred mysteries of creation’ by a common tart.

Albert did not confront Bertie directly, breaking the news of his knowledge of the son’s indiscretion through a letter. The confrontation came during Albert’s surprise visit to Cambridge on 25 November. The weather was horrible, but still father and son went for a long, private walk around the town. Details about the conversation shared between the two have been lost to history. The end result, however, was a father’s forgiveness. This new dynamic in their relationship, unfortunately, would never have a chance to develop. The chill Albert caught at Cambridge exacerbated his already fragile health that had been weakened by years of overwork and constant bouts of gastric problems. He would be dead before the New Year.

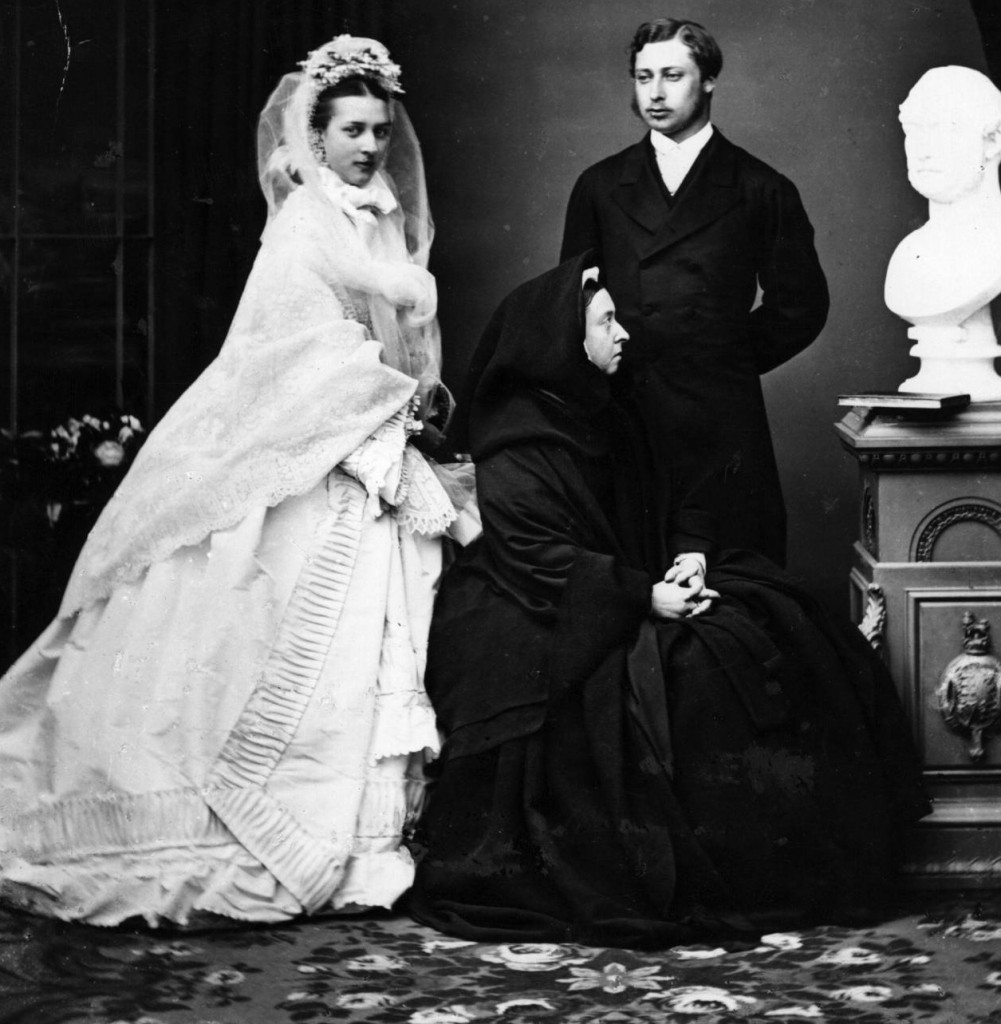

The death of the Prince Consort was a game changer in the relationship between Victoria and her children, especially Bertie. Albert’s last wishes, or those Victoria interpreted as such, became law. A tour of the Levant, originally planned by Albert as a finale for Bertie’s education, was embarked upon in February. Whether this was to fulfil Albert’s plans or to get Bertie away from her is up for debate. In Bertie’s absence, Victoria arranged a meeting with her uncle Leopold, King of the Belgians, at the palace of Laeken, in order to have Princess Alix presented to her. The young princess, wearing a modest black dress, won over the mourning Queen who gave her sanction, read as command, for Bertie to act accordingly. On 9 September, in the gardens of Laeken, the Prince of Wales dutifully proposed.

Before the newly engaged couple even had a chance to get to know one another more properly they were split apart. In November Alix was to spend a few months with Victoria and the younger children, in order to understand the life she was marrying into. Bertie, on the other hand, was sent off on a cruise in the Mediterranean with Vicky and Fritz. The marriage contract between Britain and Denmark was signed on 15 January 1863 and the date set for 10 March 1863. On the morning of the wedding Bertie and Alix accompanied Queen Victoria to the recently completed mausoleum at Frogmore. As they stood before the mortal remains of the immortal consort, the Queen brought their hands together and offered the couple ‘His blessing’. In a way, this was true for a choral piece composed by the Prince Consort was played during the service. Though the wedding ceremony in St George’s chapel was a solemn, mostly private affair, with Victoria tearfully observing the event from the royal closet, it was not without its controversy.

The heavy involvement of Vicky and Fritz in the matchmaking process further alienated them from the conservative Prussian Court, causing added strain on the relationship between Fritz and his father, Wilhelm I. Not only were Fritz and Vicky in attendance, Fritz was Bertie’s best man. The British press, for the most part, followed the government’s and Victoria’s wish that the marriage be reported as purely a love match with no political attachments. This was meant as a peace offering of sorts to Prussia and the German Confederation. The Illustrated London News (21 January 1863) did, however, make it pointedly clear where the sympathies of the British public lay. ‘It pleases us, in the present case, that the Danish people come from the same original stock as ourselves’. Despite the air of hostility, Wilhelm appeared to be in a conciliatory mood, gifting the young couple a large vase, richly gilded, with his portrait emblazoned on it. Still, his four-year-old grandson and namesake likely best expressed Wilhelm’s actual sentiments by biting the legs of his British uncles (Princes Alfred and Leopold) during the wedding.

The Marriage of the Prince of Wales with Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863 by William Powell Frith.

The marriage was to prove successful – or, at least, tolerable – despite Bertie’s carnal appetites. But, Prince Albert’s dream of an Anglo-German led ‘Family of Nations’ suffered greatly as a result of this British-Danish union. Soon after the marriage, Alix’s father assumed the Danish throne as Christian IX and this started a domino effect that would result in the Second Schleswig War in February 1864. Denmark’s defeat, at the hands of a combined Prusso-Austrian invasion force, resulted in the loss of Schleswig-Holstein. The war had a deep impact on the Danish royal house. Alix would bear an intense hatred of Germany until her death in 1925. The political situation split the British royal family into two camps: pro-Danish (Bertie and Alix), and pro-German (Queen Victoria and Vicky). In spite of this crack, the Anglo-German family ‘vase’ was not yet irreparable. It was still hoped, especially by Bertie, that Fritz’s ascession to the Prussian throne would help mend the familial bond. The rift was never healed, and was exacerbated by the untimely death of Friedrich III in 1888 – a mere 99 days into his reign.

Young Wilhelm succeeded his father and effectively destroyed the last Albertine hopes for a liberal Germany. Upon Victoria’s death in 1901, Bertie, now Edward VII, would come into constant conflict with his nephew Wilhelm II. Competition and animosity arose between the two in the area of international affairs, causing additional cracks in the familial sphere. This came to a head in 1903-4 with Bertie’s successful visit to France, which paved the way for the Anglo-French Entente Cordiale. Wilhelm, with his unstable personality, was unable to compete with his uncle’s natural charm and diplomatic ability. In addition to Bertie’s diplomatic successes, the Danish royal house had expanded, since 1864, into Greece, Norway, and Russia. By the time of Bertie’s death in 1910, the Anglo-German family network was beyond repair. The many fractures and cracks caused to the dynastic system by ever increasing nationalist rivalries ultimately contributed to the destruction of the family ‘vase’ in August 1914.

Suggested further reading:

Queen of Great Britain Victoria and Victoria, the Princess Royal, Dearest Child: Letters between Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal, 1858-1861, ed. by Roger Fulford (New York, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964)

Ridley, Jane, Bertie: A Life of Edward VII (London: Chatto & Windus, 2012)

Van der Kiste, John, Queen Victoria’s Children (Stroud: The History Press Ltd, 2010)

Wilson, A., Victoria: A Life (London: Atlantic Books, 2014)

Windscheffel, Ruth Clayton, Reading Gladstone, 1st edn (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

“The Illustrated London News.” [London, England] 24 Jan. 1863: [85].

Images 1-3, 5: www.royalcollection.org.uk

Image 4: http://theroyalfamilyofbritain.tumblr.com