The unwanted successor

Heidi Mehrkens

No adventure story without a true villain. When, in March 1848, the revolutionary movement spread and reached Berlin, crowds in the streets were convinced that the part of the scoundrel was performed by Wilhelm of Prussia, younger brother of the childless King Friedrich Wilhelm IV and heir to the throne. Prince Wilhelm (1797-1888) was targeted as a figurehead of the counter revolutionary movement. Condemned for his conservative politics and for his siding with the military, Wilhelm’s palace was attacked and his family felt seriously threatened. Public fury eventually became unbearable and following the street fighting on the days of 18 and 19 March the Prince was forced to leave the country: At the King’s bequest, Wilhelm went on a diplomatic mission – swiftly invented in order to keep up the appearance of a planned journey to London. “My situation is almost desperate!” the Prince wrote gloomily to his brother, repudiating the accusation that he had ordered troops of the Berlin garrison to open fire at demonstrators: Nothing, he protested, could be further from the truth.

Prince Wilhelm became heir to the throne in 1840, at the age of 43, when his childless brother acceded to the throne. His conservative views and opposition to the planned introduction of some constitutional elements of government did not contribute to his popularity with his future subjects. His military position as general of the Prussian infantry added to this unfavourable image. Even though King Friedrich Wilhelm IV himself was far from keen on constitutional progress in Prussia, in the 1840s growing dissatisfaction concentrated on the heir to the throne rather than on the king himself.

It is clear now that the Prince’s flight from Berlin affected his political thinking: The revolution that spared both king and heir but threatened both of them with the collapse of Hohenzollern rule seems to have taught the royal brothers a lesson, even though the decade following the counter revolution of 1849 secured the monarchical prerogative as fundamental to the new constitutional order that had been conceded. In fact, as David Barclay points out, the old order “was harsher than ever before”. Still, “politics and public life were in the process of becoming modern”, and the king and his heir both expressed their conservative point of view in different ways, gradually acknowledging elected chambers and their moderate representatives as inevitable for the political future of the Prussian monarchy.

This essay will focus on the threat to the line of succession that boiled briskly during the Prussian Revolution: The Hohenzollern dynasty had to face the fact that the tradition of hereditary principle – set in stone for centuries – seemed to have become negotiable. Very different agents and parties engaged in a dustup about whether the male royal bloodline was still accepted as the sole necessary quality characteristic of a future king – or if the royalty of the blood could nowadays be expected to be accompanied by a convenient set of (liberal) values and a favourable public image. The case of the Prince of Prussia sheds some light on expectations towards the future ruler and strategies of how to establish an idea of “modern” monarchical succession even if this collided with conservative ideas of the high-born personalities concerned.

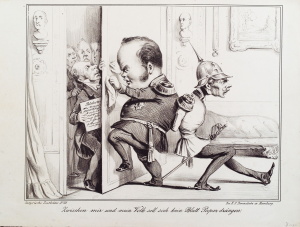

Contemporary satire on King Friedrich Wilhelm and Prince Wilhelm of Prussia struggling to shut the door in the face of petitioners: Isidor Popper (1816-1884): “No sheet of paper shall come between me and my people”, lithographic print, 1848-1849, Satyrische Zeitbilder.

His expulsion from Berlin was a severe blow to Prince Wilhelm; in his letters from London he fulminated against a conspiracy surrounding him – sinister plans carefully prepared by Friedrich Wilhelm’s court camarilla in order to replace him as next in line to the Prussian throne: “The party of movement”, he wrote to his brother, “that is the friends of the sovereignty of the people, cannot wish for more than to make a hole in the legitimate order of succession and thus to demonstrate their power.” Wilhelm felt strongly that he had been prevented from fulfilling his duty towards the King and Prussia: “I always remained true to the fatherland, I wanted to go down with you”, he complained. “Now I have to accept an – honourable – exile… why?”

In fact no-one at court could have ignored that the royal brothers were at loggerheads about how to react to the threat of the revolution. When on 13 March the military moved forward against the people of Berlin for the first time, Prince Wilhelm criticised the government’s reaction as indecisive and hesitant. He pushed for a rapid, brutal breakup of the demonstrations and petition campaigns, at gunpoint if necessary. It was for a reason he became known as “Prince Case Shot”. Having fled to the royal palace from a menacingly growing crowd beleaguering his residence, the Prince and the King signed a document on 18 March abolishing censorship, re-convening the United Diet and paving the way for a constitution. This concession, on the part of the heir, was given less than half-heartedly; Wilhelm still opposed a ministry composed of moderate conservatives and liberals and pushed for a military solution.

Street fighting at Alexanderplatz in Berlin in 1848 during the German Revolution (lithographic print).

When on 19 March, in the wake of severe fighting in the streets, Friedrich Wilhelm withdrew his troops from the city to avoid further bloodshed, the furious heir to the throne yelled at the King whom he took for a coward and a blabbermouth. Promptly the demonstrating crowds demanded that Prince Wilhelm renounce his right to the Prussian throne. The King tried to calm the situation down by publicly showing himself and paying homage to the men who had been killed during the fights and were paraded past him and the Queen: Apparently the revolution had triumphed and the monarchy had to bow its head.

The King and his newly appointed chief minister Count Adolf Heinrich von Arnim-Boitzenburg decided that Wilhelm’s bad reputation not only impeded an understanding with the revolutionary forces but might, in fact, endanger the dynasty. So by sending him away the government were willing to sacrifice the heir – at least for the time being – in order to reconcile the King with the groups within the bourgeoisie favourable of a constitution that supported a strong monarchy. By no means had this implied that Wilhelm’s right to become King of Prussia had been renounced. There was at that time no alternative, no official plan B for changing the line of succession.

In London, where he arrived on the 27 March 1848 after an adventurous flight and having left his wife and children behind, Wilhelm explored new political territory. In fact he had not much to do, except, of course, conversing and dining with the highest political circles and members of the royal family. It seems that especially Prince Albert, Victoria’s German husband, made an impression on the heir to the throne. He discussed the British monarchical system and visions of a future united Germany with him. “The poor Prince of Prussia”, Albert wrote in a letter to Prince Charles of Leiningen on 30 March, “has been shamefully slandered by a party which would gladly see the best of princes cleared out of the way. (…) He was not in favour of a change, but he is loyal and will stand or fall by the new, as he was ready to do by the old.”

In fact Wilhelm adopted some (from his perspective) fairly advanced ideas during the two months he spent in London. He was well aware that something had to be done about his reputation as an unwavering hardliner in order to prepare his triumphant return to Prussia. In Berlin the first constitutional government had lasted only ten days. On 29 March the liberal Cologne businessman Ludolf Camphausen became first minister; the entrepreneur David Hansemann was appointed finance minister. In April, the young ministry Camphausen/Hansemann prepared elections for both a Prussian and a German National Assembly. Their main task would be to approve constitutions for Prussia and a united Germany.

After his favourite plan – to be given a military command – had failed, Wilhelm instead adopted Prince Albert’s idea that all German Princes should actively shape Prussian and German politics rather than refusing to play a part in a changing political environment. Prince Wilhelm intended to become a representative of the Prussian National Assembly – provided there would by a clear chance of a successful election; otherwise he expected a devastating effect from furious press campaigns on his already shaken public image. The Prince was elected in the tiny constituency of Wirsitz in Posen and impatiently prepared his return to Berlin in time for the opening session of the National Assembly.

“I think we can dare to bring him back”, King Friedrich Wilhelm announced in a written conversation with Camphausen at the beginning of May. According to the king, his younger brother deserved every effort to be re-established in Prussia: Having suffered personally and experienced gross insult, Wilhelm nevertheless had declared his willingness to accept the new political course. Not to mention his importance for the crown and the future of the dynasty.

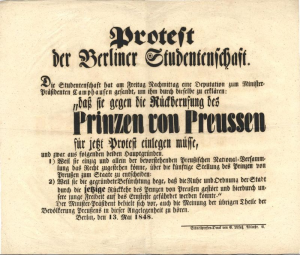

Protest of the students of Berlin against the return of the Prince of Prussia, 13 May 1848 (Historic Collection, Library of the Humboldt University Berlin).

On 10 May the ministry Camphausen officially recommended the King to cut short Prince Wilhelm’s stay in London in order to allow him to be in Prussia for the approval of the new constitution. When the King confirmed that the Prince of Prussia would be returning soon, the public outcry in Berlin was enormous. With demonstrations of 10.000 men and women in the streets, petitions, public speeches and charivaris revolutionary forces sought to undermine the decision. A popular folk song announced unmistakably:

“Master Butcher, Prince of Prussia,

dare come, dare come to Berlin.

We will throw stones at you,

And mount the barricades!“[1]

Camphausen and his fellow ministers were threatened, yet the monarch was adamant: Every step back would now endanger the succession and with it the Prussian throne; and Friedrich Wilhelm had no intention of negotiating the ancient rules of succession – neither with the crowds in the streets of Berlin nor with the National Assembly. If matters of the Hohenzollern succession would be dragged before the National Assembly, then, he stated, “I should send this assembly packing, and if the city supports this cause, then weapons will do the talking!”

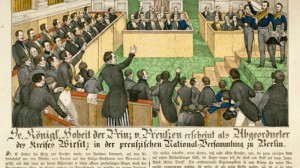

The Prince of Prussia as Representative of Wirsitz in the National Assembly, 8 June 1848 (“Berliner Zeitung”, Multimedia Archive).

Luckily, when Prince Wilhelm made his carefully prepared entrance in the Prussian city of Magdeburg on 6 June, he was greeted with cheers and comforting applause and not with stones. For the time being the situation had calmed down. Two days later Wilhelm made his appearance in the National Assembly and gave a short and rather stiff speech, confirming his loyalty to this new form of government that had been granted by the King. It was his last official act as representative of Wirsitz. A year later Wilhelm would personally command troops to invade the southern duchy of Baden and crush republican forces. Still, the upheavals of the revolutionary years had clearly left their mark on the Prussian monarchy and on the unwanted heir and villain. He had suddenly found his position within the dynasty a matter of public debate. The great pains taken to improve the heir’s image, by himself as well as by others, clearly show that the Prussian royal family was aware of their new public role and that it mattered for the future King to be accepted – even loved – by the people.

Further reading:

David E. Barclay, The Court Camarilla and the Politics of Monarchical Restoration in Prussia, 1848-1858. In: Between Reform, Reaction, and Resistance: Studies in the History of German Conservatism from 1789 to 1945, ed. by Larry Eugene Jones and James Retallack, Oxford, Berg, 1993, p. 123-156.

Christopher Clark, The Iron Kingdom. The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947, London, Penguin, 2007.

Ute Frevert, La politique des sentiments au XIXe siècle, in: Gudrun Gersmann, Mareike König and Heidi Mehrkens (ed): L’espace du politique en Allemagne au XIXe siècle. Revue d’histoire du XIXe siècle, n° 46, 2013/1, p. 51-72.

Letters of the Prince Consort 1831-1861, selected and edited by Kurt Jagow, London, Murray, 1938.

Frank Lorenz Müller, Die Revolution von 1848/49, 4. Edition, Darmstadt, WBG, 2012.

[1] „Schlächtermeister / Prinz von Preußen / Komme doch, komme doch / nach Berlin / Wir woll‘n dir / mit Steine schmeißen / und auf die / Barrikaden ziehn.“