See also: “Our four heirs to the throne”

A tale of two princes

Miriam Schneider

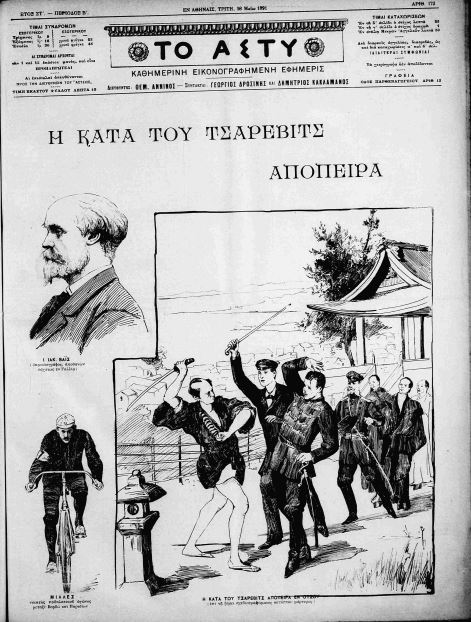

On 6 May 1891 [OS, 18 May 1891 NS], the Athenian newspaper Asty recounted a current news story by resorting to the colourful imagery and language of the fairy tale. It told of “two princes” who had travelled to “a faraway country” of mythical fame:

“One of the princes”, the anonymous author explained, “originated from a great, prosperous realm. The homeland of the other was small and weak, although it once had been powerful and glorious. Strangely, though, the prince who came from the mighty kingdom was small and delicate, whereas the other was strong and full of vigour”.

“The two princes”, the story went on, “travelled the world together until one day they arrived at a strange and wild place. Everything in this place was small, small, but well-formed. […] The houses, the trees, the men, the women. One evening, they strolled along the side of a lake […] when suddenly two locals appeared and attacked them with their knives. One of them dealt a terrible blow to the delicate prince, and his blood began to stream. When his companion saw this, however, he turned on the villain, dealt him a blow with his walking stick, a strong cane made from the oak trees of his country”, and thus saved the delicate prince’s life.[i]

This romantic story referred to the so-called “Otsu incident” which occurred during the “eastern journey” of Tsarevich Nicholas of Russia, the future Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918). It was all over the European news in early May 1891. A fanatical policeman had tried to assassinate the Russian heir to the throne while he was on a touristic excursion to the Japanese countryside near Lake Biwa. Luckily, though, his cousin and travel companion, Prince Georgios of Greece (1869-1957), had prevented further harm by striking the assassin down with his walking cane.

In the idiosyncratic view of the Greek newspaper, the relatively small height (1.7 metres) and slender figure of the Russian heir to the throne were contrasted with the huge build and bearlike strength of the Hellenic prince. This allowed the Greeks, for ever struggling to be accepted as full members of the European concert of powers, to implicitly reverse the power relations between their insignificant nation on the one, and their mighty friend, the Russian Empire, on the other hand. That the high hopes the Greeks so often put into the dynastic connections of their royal family never materialized, has already been the gist of another “Heir of the month”, the “Prussian Duke of Sparta”.

This is not another tale of failed political hopes. Rather, it is a story about a journey and an unusual assassination attempt and the many different angles from which they can be viewed. It shows how one journey, largely through the turn it took at Otsu, ended in two fundamentally different ways for two travelling princes. For the delicate heir of a mighty throne, despite his encounter with death, the “eastern journey” was an exotic grand tour which introduced him to the Oriental other – or self – of imperial Russia and “awoke” him “to promises of glory and greatness” in the East.[ii] Historians have frequently pointed to it as an explanation for the erratic imperialist policies that characterized Nicholas’s early reign and the coming about of the Russo-Japanese War (1904). For the vigorous prince from insignificant Greece, however, what started as a pleasure cruise, despite his gallantry at Otsu, ended as a walk of shame as much as fame. It was one of a number of incidents which would finally convince Georgios that, like Greece, he was ultimately travelling alone.

Nicholas’ tale – Oriental encounters

In October 1890, the 22-year-old Tsarevich Nicholas of Russia, together with a large entourage, started out from St Petersburg on what would become a 10-month grand tour through Asia on board the cruiser Pamiat Azova. It would take him to Egypt, India, China, Siam, and Japan, culminating in the festive inauguration of the building works on the eastern section of the Trans-Siberian Railway near Vladivostok in May 1891.

Though unconventional in comparison with normal 19th-century grand tours, the cruise was neither exceptional nor illogical. In the Age of Empire, an increasing number of European royal princes travelled to the Far East: be it that they progressed through the imperial realms of their illustrious families, as British princes did on their royal tour; or be it that they were more generally introduced to the fascinating exoticism or future possibilities of this latest area of imperialist rivalry, as Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary (1892) or Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany (1912) were. Nicholas, by travelling east, could get an impression of the vastness of his future realm, represent his dynasty to Russia’s eastern neighbours, and, as heir to the throne, demonstrate his father’s active support of a still contested infrastructure project.

Tsar Alexander III’s determination to tie the eastern parts of his Empire closer to its core by way of a railway was mainly part of a strategy of domestic consolidation, centralization, and Russification. It can also be seen within the context of a wider eastward turn, though, which influenced intellectual and political life in fin-de-siècle Russia. By the late nineteenth century, many Russian intellectuals and nationalists had grown disappointed with the intellectual-political developments in Western Europe (democracy, rationalism, materialism, and atheism). Realizing at the same time that the Westernizers’ dreams of catching up with Europe’s material progress were futile, these voices increasingly conceptualized Russian national identity as fundamentally distinct. Some turned to Slavophilia, the positive affirmation of Russia’s Slav heritage and her destiny as the liberating force of all the Slav peoples living in the Balkans. Others turned to Asianism. They believed that both Russia’s roots and her future lay in Asia, that there was a special “spiritual kinship” between the Asian peoples (visible e.g. in their religion or acceptance of autocracy), and that it was the tsar’s historical mission to reunite them. Both ideologies influenced Russia’s foreign policy and continental imperial expansion in the late 19th century.

Nicholas’ tutor on the grand tour, Prince Esper Ukhtomsky (1861-1921), a dilettante Orientalist working for the Interior Ministry’s Department of Foreign Creeds, was a prominent representative of the Asianist vision. His presence in the imperial entourage reveals how the tour was not only meant to present the future tsar to the other players in the Eastern imperial game, but also to acquaint him with the Asian civilizations bordering on Russia. The enthusiasm and respect Ukhtomsky entertained for the non-Russian nationalities within and outside the Empire as well as for non-Orthodox faiths such as Buddhism clearly also shaped Nicholas’ perception. In his letters home, the grand duke frequently admired Asian culture as unsullied by European influences.

Nicholas’ emotional highlight was undoubtedly his stay in Japan. “Only a few days here and I’m absolutely in heaven”, he reported home on 21 April 1891.[iii] Although conflict over Korea was already on the horizon, relations between the two countries were friendly at the time. The Japanese, eager to be treated as equals by the European great powers ever since the Meiji Restoration and its programme of Westernized reforms, wanted to show their “regard for [their] great northern neighbour”. They therefore prepared a “magnificent welcome” for the Tsarevich, the highest-ranking royal visitor to date, “marked by all the heartiness, grace, and novelty which the Japanese are so well able to impart to these occasions”.[iv]Nicholas was enthusiastically received on the streets, lavishly entertained by the Imperial princes, and watched displays of sumo wrestling, kendo, and samurai drill.

One of the more realistic depictions of the Otsu Incident: P. Ilyshev, The attack on the Tsarevich (http://www.lifo.gr/team/sansimera/38197)

Following his stay at the ancient capital of Kyoto, however, on a touristic excursion around Lake Biwa on 29 April [OS; 11 May NS] 1891, one week after Easter, the prince was attacked by a Japanese policeman while passing the streets of Otsu. For the sake of dramatization, pictorial and written representations of the scene – such as the fairy-tale from Asty – later often depicted the Tsarevich and his cousin standing and relatively alone. In reality, though, their entire party were riding in a procession of rickshaws pulled by Japanese coolies, and the streets were lined with spectators and police. Unlike Europe, which was plagued by anarchist assassinations throughout the 1880s-1890s, Japan was considered a safe place for tourists. Therefore, it came as a shock when suddenly one of the policemen, Tsuda Sanzo, darted forward and hit Nicholas with his sabre.

His motivations were subject to many speculations. Some thought him insane. Others believed he was inspired by a hatred of everything foreign – a trend particularly virulent among the Japanese samurai caste and inducing both the imperial court and Europe’s foreign offices to be more cautious about royal visits in the subsequent years. An adventure book published by the German Major von Krusow in 1898 (Die Fahrten und Abenteuer des Thronfolgers Nikolaus von Russland in Japan / The travels and adventures of Tsarevich Nicholas in Japan) even construed a plot where the assassin was hired by Russian anarchists. Most probably, though, Tsuda’s motives were a mix of frustration about his humble status as a policeman (compared to his former career as an officer), anger at Nicholas’s irreverent behaviour near a memorial for dead soldiers, and an irrational belief that he was a Russian spy.

An inventive adventure story: Major von Krusow, Die Fahrten und Abenteuer des Thronfolgers Nikolaus von Russland in Japan, 1898 (Author’s collection)

When Nicholas, feeling a “sharp sensation on my right temple”, turned round, according to his travel journal, he beheld “a policeman, so ugly as to turn my stomach […] swinging a sabre in both hands and coming at me for a second attack.” He jumped from the rickshaw, and, since no one seemed to stop his pursuer, “ran as fast as I could”. He “wanted to hide in the crowd”, but, as will happen in such moments of terror, “the Japanese had panicked and were scattering in all directions.” Only when he turned again, did he spot his cousin Georgios, who apparently ended the attack by hitting the madman with his walking stick.[v]

Luckily, the wound that Nicholas received in this surreal situation was slight. It caused quite some stir in the European press, though, shocked Russia, and particularly upset his hosts. The entire Japanese nation felt that this first attempt to assassinate a royal personality on their soil was an “indelible stain fixed upon [their] history”.[vi] On the one hand, the Japanese feared that Russia might retaliate with military force – which, however, was never the intention of the peace-loving Alexander III. On the other hand, they were afraid that the West might see this as a sign of Japan’s continued barbarity precluding friendly terms with any civilized nation. The Tenno, therefore, went to unusually great lengths to apologize to his imperial guest, immediately taking the train to Kyoto and even accepting a refusal to meet Nicholas on the first night. Sanzo’s trial would become a downright power struggle between Meiji and the Japanese judiciary. The Emperor, eager to show his kinship with Europe’s royal houses, wanted the death penalty – reserved for violations against the Tenno only by Article 116 of the Criminal Code. The special court convened, however, successfully defended the independence of the judiciary, passing a sentence of lifelong imprisonment instead. The “Otsu incident” would thus go down in Japanese annals as a momentous step in the history of law – as well as in the history of public opinion and the press, since the Japanese newspapers took great interest in both the incident and the court trial, fighting against official censorship.

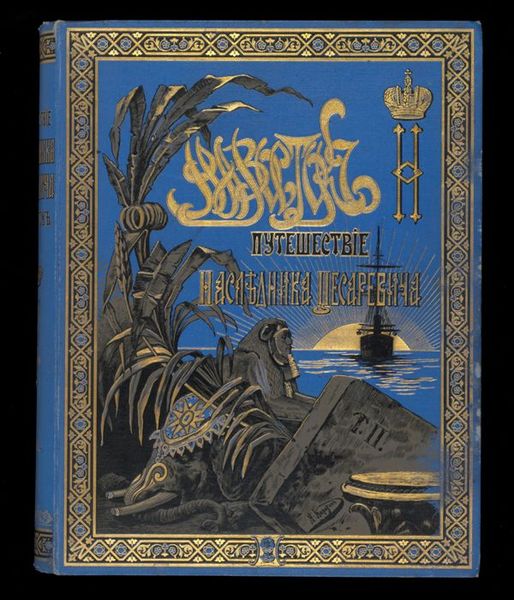

Surprisingly, the Russian government accepted both the Japanese apologies and the sentence without further ado. Even Nicholas, though he had to leave Japan earlier than planned on request of his parents, retained “no hard feelings” [vii], regarding the incident as the deed of a fanatic individual. According to most historians, he even returned from his journey with a decided love for the mysterious Orient, “clearly in awe of the Asian realms he stood to inherit”[viii] and, in “his juvenile imagination” playing “with grandiose ideas”[ix] about the wider Far East. Prince Esper Ukhtomsky’s travelogue, written in close consultation with Nicholas, published in two lavish volumes (1893-1897), and broadly distributed through the special efforts of the imperial family, could be understood as a manifest of both men’s Asianist vision. It propagated the idea of the “White Tsar” as a pan-Asian ruler and foreshowed the expansionist policy Nicholas, influenced by his Asianist and imperialist advisors, would adopt after his accession in 1894.

Asianist manifesto: Prince Esper Ukhtomsky’s travelogue “The Account of Travels Made by His Imperial Highness Tzesarevich to the East” was translated into English, German, and Chinese, among others

This policy veered between the protection of China and territorial expansion at its costs, and it finally ended in a disastrous war against Japan (1904) when the territorial ambitions of the two expanding nations clashed over Manchuria and Korea. Some of Nicholas’ Russian contemporaries would interpret this war as a late revenge for the events of 1891. According to the historian Rotem Kowner, though, the tsar’s attitude towards Japan was a blend of “Orientalist fondness” and racial prejudice which led to an “underestimation of the Japanese national character and military capability”. During his stay, Nicholas, like many European travelers, had formed an impression of the Japanese as an effeminate, childish, and biologically inferior race. The entire nation was associated with sensual Geishas, perceived as physically small in contrast to the “Russian giants”, and even called “little monkeys”. After his return, these impressions developed into a cognitive “schema”, which would finally influence Nicholas’ assessment of Japanese military power. The defeat of the Russian Fleet at the hands of Meiji’s far from backward forces came as a shock to the young tsar whose autocratic rule stood itself in sharp contrast to his “delicate” physique. They ended the period of Asianist dreams that had begun in 1891.

Georgios’ tale – Travelling alone

The flipside of Nicholas’ “eastern journey” was the story of his cousin, Georgios of Greece, in many ways representing the “dark side” of both the “grand tour” in general and this grand tour in particular.

Georgios had joined the Pamiat Azova in Athens in November 1890 in the official capacity of a Lieutenant Commander. Trained in Denmark, his stint in Russian services was to further prepare him for his role as a naval officer of the young Greek navy. That he should join the Tsarevich on his tour was only logical, as he was both maternally and paternally closely related to the Russian Imperial Family. Also, his nation shared Russia’s fate of being torn between East and West. Striving to be accepted as a “civilized” country by virtue of her ancient heritage, Modern Greece was frequently labelled a backward Oriental nation by the European powers. Russia was her main ally in the pursuit of her irredentist ambitions against Turkey.

This illustration published by Asty on 28 May 1891 had originally been published in the French Le petit Parisien before.

Famous for his tall build and Herculean strength, Georgios would reach his moment of fame when his cousin made his encounter with death. His version of the Otsu incident in the shape of a letter to his father, King George of Greece, was published in the Danish paper Berlingske Tidende in May 1891 and then went viral around the world. Hearing “something like a shriek in front of me” and seeing his cousin pursued by his Japanese would-be assassin, Georgios jumped out of his rickshaw and followed him. In his terror, the Tsarevich “ran into a shop, but ran out again immediately, which enabled the man to overtake him. But I thank God that I was there in the same moment, and while the policeman still had his sword high in the air, I gave him a blow straight on the head […]. He now turned against me, but fainted and fell to the ground.” Two rickshaw pullers subsequently finished off the assassin.[x]

Although Georgios, according to other testimonies in the Japanese court trial, did not decisively knock out Suda before the rickshaw coolies came to his assistance, he was immediately celebrated as his cousin’s sole saviour. Emperor Meiji thanked him for having guarded “Japan’s history from a stain which could never have been blotted out”. His crew had his walking cane engraved with the memorable date. All over Europe and the world, but especially in Greece, the newspapers were full of praise for his “gallantry”. Colourful lithographs depicted the scene in imaginative variations. According to the German Minister in Athens, Georgios’ deed was “extolled in all the papers and regarded as a new bond with which providence has tied these two closely related and friendly royal houses closer together”.[xi] Asty, in the article cited above, recounted how Georgios’ name “passes from mouth to mouth like a foreboding of glory and happiness, like a greeting from and a guarantee for the future”.[xii]

While he was publicly celebrated in Europe, however, Georgios was privately expelled from the Tsarevich’ entourage. Instead of accompanying Nicholas all the way back to St Petersburg, as originally planned, he was ordered home via telegram from Vladivostok. As his brother, Crown Prince Constantine, confidentially told his former tutor, the German General Consul Lüders, this departure was “not at all on his own initiative”, as officially stated; rather, the Russian court had advised Georgios “to continue his journey alone and without trespassing Russian soil.” What had happened?

According to Constantine, the Tsarevich’ entourage, particularly his aide-de-camp Prince Baryatinsky, could not forgive Georgios that he alone had come to Nicholas’ rescue. They had intrigued against the prince at the Russian court and called forth the relevant telegram. Tsar Alexander, who did not even express his gratitude to his brother-in-law, King George of Greece, was also supposed to have been furious about the publication of Georgios’ letter, in which he publicly depicted the Tsarevich as running away from the aggressor. Emperor William II, on reading the report, scribbled down a few marginalia giving more insights. He was convinced that Georgios had been “given the chop for his misconduct”. As he knew from his aunt, the Duchess of Edinburgh, née Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, “Georg Hellenios […] has proved so tactless, without manners or bounds that everyone was appalled at his misbehaviour, clownish nature, and silly pranks”. Since he was considered a bad example for the future tsar, he was sent packing.[xiii] According to Georgios’ later wife, Marie Bonaparte, the false reports sent home to the Russian Court accused the Greek prince of having dragged Nicholas to disreputable places and having encouraged him to violate the sanctity of a temple.

It is hard to ascertain which side of the reports was right. Georgios, known to be a “man of the people”, had indeed, and famously so, introduced his cousin to the taverns of Athens in November 1890. Both from Nicholas’ diary and from Japanese police reports we know that he and his entourage frequently slipped away to go on visits on shore during their journey, even during the week before Easter, being entertained by Geishas and maybe also prostitutes. However, the initiative for these visits came both from the Russian officers on board and from Nicholas himself, who had been told about Japanese women by one of his naval cousins and was out to enjoy himself. The “dark side” of the grand tour was a tacit understanding that highborn European youths would be able to “sow their wild oats” in the relative anonymity of faraway places. In how far Prince Georgios, who, according to his later wife, was not even interested in women, could be held responsible for the digressions is impossible to judge.

Nevertheless, the prince had to leave the party in disgrace, travelling home alone via New York and London – where he was not received by Queen Victoria. Only on 30 July 1891 was he finally embraced by his paternal grandfather, King Christian IX, in Copenhagen.

According to Marie Bonaparte, the disgraceful end of Georgios’ eastern journey was one of a series of experiences which left him a scarred and embittered man. The second event, the so-called Cretan Drama, was strangely involved with the first one. In 1897/98, Tsar Nicholas II, feeling eternally indebted to his cousin for his rescue and sorry for his subsequent unfair removal, decisively supported Georgios’ installation as High Commissioner of the semi-autonomous Cretan State. For years, the Cretans had been struggling for independence from the Ottoman Empire and unity with the Kingdom of Greece. Georgios’ election after another insurrection and the subsequent – disastrous – Greco-Turkish War, represented a significant step towards this goal and a late prove of Asty’s predictions. Unfortunately, though, the prince, being formally a servant of the Ottoman Sultan, was unable to fulfil the hopes for complete re-union. By 1906, not even his friend and cousin Nicholas, troubled by the consequences of the Russo-Japanese War and the subsequent Revolution of 1905, would be able to help. The man who had been hailed as a “messiah” by his Cretan subjects had to secretly be rescued from the isle by a British cruiser. He would never recover from the shame, withdrawing to France and Denmark and to a shell of embittered loneliness.

Fairy tale endings?

The above-mentioned article from Asty, by resorting to the language of the fairy tale, implied a happy ending for the poorer, but abler prince and his small, but once glorious country. In 1891, this twist did not come true for Prince Georgios. In the long run, however, he proved to be more fortunate than his cousin. For while the delicate prince with the scar in his face, due to no small degree to the erratic policies of his first decade in office, would finally end his life in the turmoil of the Russian revolution (aged 50), the giant prince with the scar on his soul died the longest-living member of his dynasty in 1957, at 88.

Suggested Further Reading:

- Bertin, Celia, Marie Bonaparte: A life (New York, 1982).

- Holland, Robert, ‘Nationalism, Ethnicity and the Concert of Europe: The Case of the High Commissionership of Prince George of Greece in Crete, 1898-1906’, Journal of Modern Greek Studies 17/2 (1999), 253-276.

- Huffmann, James L., Creating a public: People and press in Meiji Japan (Honolulu, 1997).

- Keene, Donald, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his world, 1852-1912 (New York, 2002).

- Kowner, Rotem, ‘Nicholas II and the Japanese body: Images and decision making on the eve of the Russo-Japanese War’, The Psychohistory Review 26, 211-252.

- Marcopoulos, George, ‘The Selection of Prince George of Greece as High Commissioner in Crete’, Balkan Studies 10 (1969), 335-350.

- Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, David, Toward the Rising Sun: Russian Ideologies of Empire and the Path to War with Japan (DeKalb, Illinois, 2001), Chapters 1 and 3.

- Skandamis, Andrea, Πρίγκηψ Γεώργιος, η ζώη και το έργον του (Athens, 1955) [Prince Georgios. His life and his works]

- Utz, Raphael, ‘Die Orientreise Nikolaus II. und die Rolle des Fernen Osten im Russischen Nationalismus, in Sprotte’, Maik H./Seifert, Wolfgang/Löwe, Heinz-Dietrich, Der Russisch-Japanische Krieg, 1904/05: Anbruch einer neuen Zeit? (Wiesbaden, 2007), 113-145.

[i] Anonymous, Prince Georgios, Asty, 6.5.1891.

[ii] David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, Toward the rising sun, 5.

[iii]The diary of Tsarevich Nicholas II, cited by Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, 18.

[iv] Henry Spencer Palmer, The Attack on the Czarevitch in Japan, The Times, 13.6. 1891.

[v] The diary of Tsarevich Nicholas II, cited by Keene, Donald, Emperor of Japan, Meiji and his world, 449.

[vi] Jiji Shimpo (Japanese newspaper), cited by Henry Spencer Palmer in the Times, 13.6.1891.

[vii] Tsarevich Nicholas cited in Schimmelpenninck, 19.

[viii] Schimmelpenninck, 20.

[ix] Constantin de Grunwald, Le Tsar Nicolas II (Paris, 1965), 123 ,cited in Schimmelpenninck, 21.

[x] ‘The attack on the Czarevitch. Prince George’s narrative”, The Star, 25.7.91.

[xi] Minister Plenipotentiary Wesdehlen to Chancellor Caprivi, 17.5.1891, Archives of the German Foreign Office, The Greek royal family, R 7476.

[xii] Asty, 6.5.1891.

[xiii] Report, 16.8.91, Archives of the German Foreign Office, The Greek royal family, R 7476.