Monarchy and Motorcars

Heidi Mehrkens

On 18 March 1913 Edward Albert Prince of Wales – known to the family as David – arrived at Cologne. Having endured a tiresome journey on the night train, he was not in the best of moods: “The Germans are very odd”, he somewhat crankily wrote in his diary, “nearly all the men wear some uniform, & they all have moustaches & smoke cigars. I hope this trip will be a success.” The eighteen year old heir to the throne, then a student at Oxford University, travelled through the German states twice in spring and summer 1913 in order to learn the language, to explore the cultural attractions and to spend some quality time with his royal relatives at various German courts.

It seems that the chock-a-block programme – his days filled to the brim with sightseeing, studies and the evenings with endless theatre and opera performances – occasionally got on the Prince’s nerves. He enjoyed his tours about the countryside and liked some of the modern plays, but Wagner’s Rheingold was not his cup of tea and, as he put it, “such a waste of time.” David, who travelled incognito as Earl of Chester, was accompanied by his tutor Professor Hermann Georg Fiedler (1862-1945) and his equerry Major William George Cadogan (1879-1914). In their company the Prince of Wales travelled via Bonn, Koblenz and Wiesbaden to Darmstadt (where he spent Easter with Grand Duke Ernst-Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt and Grand Duchess Eleonore), Heidelberg and Karlsruhe. There he stayed with Grand Duke Friedrich II and Duchess Hilda of Baden before reaching his final destination Stuttgart, where he received a warm welcome from Wilhelm II King of Württemberg and Queen Charlotte.

At second glance, the Prince found a lot to like about Germany, one thing in particular: “So ends my motor trip of 671 miles”, David’s diary proudly records on 27 March 1913. In fact, the Prince of Wales travelled all the way from Cologne to Stuttgart by car, and for a good deal of the road trip he was behind the wheel himself.

By the early twentieth century the fabrication of motorised vehicles slowly passed out of the experimental state; they had become reliable and comfortable enough to carry passengers over longer distances. The young British motoring lobby tried its best to campaign for this promising industry. Prince Edward’s interest in motorcars, it is fair to say, ran in the family: In February 1896 the freshly founded London “Motor Car Club” at the Imperial Institute was visited by King Edward VII, then Prince of Wales. As the Court Circular reported, “His Royal Highness inspected the motor carriages […] and personally tested their capabilities by riding in them at various rates of speed and on steep grades.” The Prince of Wales then officially opened the first international “Exhibition of Horseless Carriages” in London in May 1896.

Later that year the Motor Car Club organised the so-called Emancipation Run from London Hyde Park to Brighton (which is a famous vintage car rally today) to celebrate the 14 November 1896, when the Locomotives on Highways Act came into operation. This Act removed the speed limits which had so far restricted the use of motorised vehicles in the UK, and motorcar enthusiasts were now allowed to drive their electric-, steam- or petrol-powered vehicles at 14 mph. The enthusiastic Prince Edward bought his first car in 1900 and a second one in 1902; both were manufactured by the Daimler Motor Company Limited. David’s grandfather thus became an influential patron of the young British motorcar industry; a relationship from which both sides only stood to gain.

Throughout the Edwardian era motoring remained a domain of the rich: a motorcar was a luxury good. While Henry Ford gradually prepared the US market for less expensive automobiles aimed at middle class families, car owners in Britain had to be wealthy enough to afford the motor’s maintenance, high taxes and the salary of both a mechanic and a chauffeur. In 1905 there were sixteen thousand private cars on British roads; however, large-scale production of cheaper cars would not begin until the interwar period.

The first Royal car 6 hp 2-cylinders 1527 cc fitted with a "mail phaeton" body purchased by the Prince of Wales in 1900

Many European royal families not only shared the interest in the new mode of travel but used the expensive motorcars as a means of representation. The London Times informed its readers in January 1901 that Leopold II, King of the Belgians, had ordered “another electric motor-car of 20-horse power, which is expected to attain a speed up to 55 miles an hour. His Majesty, who has a great liking for this form of travel, frequently drives in the suburbs of Brussels and round the Bois de la Cambre in the neighbourhood of the city.” The above mentioned Grand Duke of Hesse drove a car in 1901, and motoring soon became popular amongst the Hohenzollern family as well. Their motoring pioneers were Crown Prince Wilhelm and Prince Henry of Prussia who bought the first car for the royal family in 1902. In 1912 Prince Henry would own some 19 motorcars, most of them Daimlers, and at least one motorcycle. His brother the Emperor remained a motor sceptic at first; in 1904 Wilhelm, too, bought a motor, following in the footsteps (or rather skid marks) of his Uncle Edward and the Tsar. In 1904 the Kaiser also became an honorary member of the German Automobile Club which, only a year later, was renamed in Imperial Automobile Club. Wilhelm built up his vehicle fleet and owned 25 cars in 1914; with fifteen chauffeurs at his disposal.

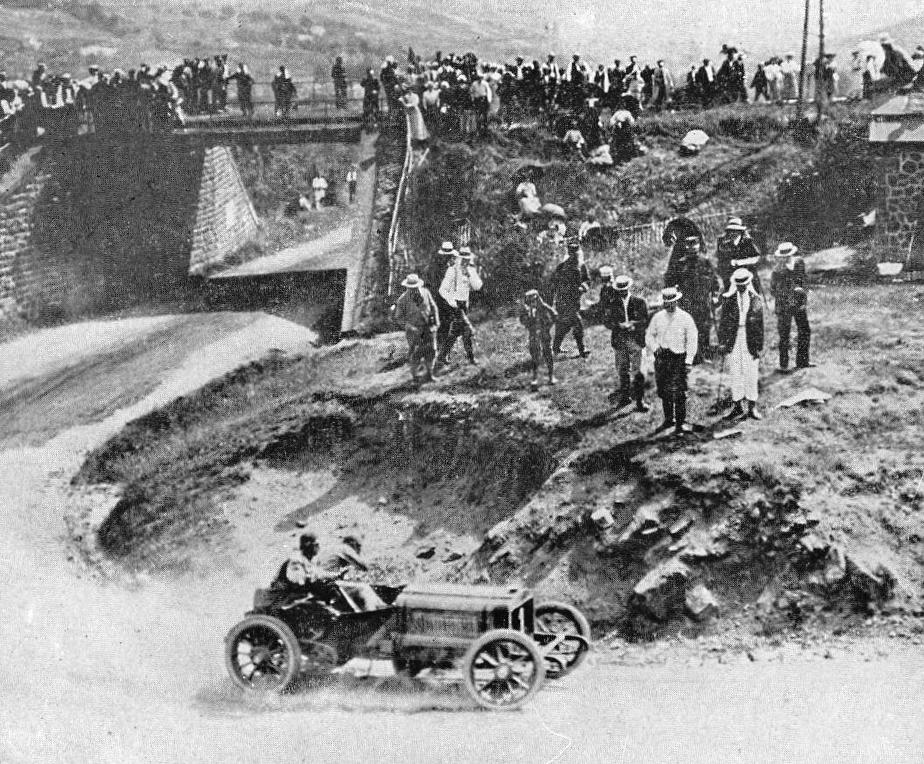

With their fondness for motoring the European royal community greatly boosted the campaign for acceptability and respectability of motorcars. They honoured motor clubs with their membership and motorcar exhibitions with their presence, photographs of royals sitting in the backseat or driving a car adorned the front cover of The Car Illustratedmagazine; they attended touring car rallies and donated prizes for racing competitions. In 1907, Emperor Wilhelm II sponsored the first “Kaiserpreisrennen” (the Emperor’s prize rally) in the Taunus area.

The fascination of the upper class Edwardians for mobility was eternalized – and mocked – in many plays and novels. Kenneth Grahame’s children’s book “The Wind in the Willows”, first published in 1908, features the adventures of Mr Toad of Toad Hall, the rich village squire and “Terror of the Highway” in his large and expensive motor car “before whom all must give way or be smitten into nothingness and everlasting night.“ Indeed, motorcars gradually changed societies as more and more of these luxury goods could be seen on roads that were not really suited for an increase in traffic. Road safety became an issue. The growing number of motorcars affected infrastructures and changed life in urban communities as well as in the city. With drivers not always in control of their cars and a population not used to sharing the roads with noisy, speeding vehicles, accidents were bound to happen. Stories of frightened horses bolting in front of motorcars, dogs and children hit by vehicles going way over the speed limit and road users ending up in hospital or even dead filled the papers. A debate in the House of Commons about the acceptable speed for motorcars resulted in the Motor Car Act of 1903. It introduced registration of motorcars and licensing of drivers in the United Kingdom and increased the speed limit to 20 mph. Similar regulations were established on the continent yet the relationship between motorcar owners, their chauffeurs and other road users should remain tense as is proved by the bitter discussions of liability laws and luxury taxes.

The royal motoring pioneers had different reasons to engage with this emerging mode of travel. Prince Henry of Prussia was excited about new technologies. When his first car broke down during a road trip in 1902 (still a frequent event in those days), Henry tried to fix the machine together with his mechanic. Afterwards the Prince was told off by Emperor Wilhelm who did not consider getting his hands dirty on a car in public acceptable behaviour for a member of the royal family. A keen horseman in spite of his crippled left arm, Wilhelm II always took the backseat in a motorcar and let his chauffeur do the driving. Other royal motor enthusiasts, including Edward VII and his grandson David, the future Edward VIII, on the other hand, enjoyed driving themselves – preferably at a considerable speed. They loved the hands-on experience of sitting behind the wheel. Driving a car developed into a fashionable new gentleman sport.

The Prince of Wales explained the benefits of driving in a letter to his father King George V from Neustrelitz on 25 July 1913: “I am very fond of driving a motor & it is a real pleasure to me & is one of the few forms of so called sport that I can get here. It makes such a difference when I go for some motor expedition from Strelitz whether I am driving or sitting behind. I also think that apart from anything personal, driving a motor is good for one’s nerve and makes one resourceful, & as I shall probably have a good deal of motoring to do in my life it does relieve the monotony of a long journey if one drives oneself. And one can only drive well, by driving constantly & getting experience.”

The Prince of Wales had probably heard this advice many times from his own driving instructor, Undecimus Stratton (1868-1929), the successful manager of Daimler’s London depot. In 1911 Stratton spent a few weekends at Sandringham tutoring David on the workings and driving of a motorcar. On longer trips, like the ones in Germany, the Prince was accompanied by his chauffeur and they would take the wheel in turns.

All royal families were well aware that driving a motorcar was not without risks. In 1911 Prince Henry of Prussia was injured in a serious accident. In May 1912 Prince George of Cumberland, eldest son of the Duke of Cumberland, was tragically killed in a car crash when travelling from Prague to Copenhagen to attend the funeral of his uncle, the late King of Denmark. The motorcar came off the road, hit a tree and was wrecked. It seems therefore perfectly understandable that King George and Queen Mary were worried about their eldest son’s safety whenever David went on a motor journey. He was their beloved child, and he was also the heir to the British throne.

The Prince of Wales’s second trip to Germany in 1913 began on 1 July, when he travelled to Munich. Journeying via Nuremberg and Prague the party took a leisurely ten days to motor to Dresden. On 10 July, David was behind the wheel when his car approached a junction at about 40 mph. His diary states: „I slowed up, blew the horn & as it was clear went on. At the same moment the horses of a farm cart bolted across & it looked as if all was up. But Cracknell [the chauffeur, HM] jammed the wheel over so that we missed the cart, but struck a tree which only smashed the left foot board & a tool box!! So we had a very lucky escape & but for the tree we should have capsized. I was awfully sick about it though it was really bad luck.”

It could already be expected that unpleasant consequences would follow hard on the heels of this incident. On 21 July, while David stayed in Neustrelitz with the Grand Duke Adolf and Duchess Elisabeth of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, he made a furious entry in his diary: “I had bad news. Some bloody man has let out about the accident on the way to Dresden on July 10th & Papa is very sick & has stopped my driving. It is disgraceful that people come between Papa & myself & report matters which I should do; all these beastly court officials do nothing but make trouble. I think it is Cracknell who wrote home, when he said he would not say anything!!”

The Prince of Wales in March 1913 outside the Zeppelin works at Friedrichshafen, in the back of a Pierce-Arrow automobile. Ferdinand von Zeppelin is standing to right in a white cap. Professor Fiedler is standing in the automobile

The Prince’s reaction reveals the frustration he felt about being constantly surrounded by his valets, tutors and bodyguards. Naturally communication between the ruler of the British Empire and his heir cannot be compared to any other relationship of a father and his teenage son. It was filtered through many official and unofficial channels and the Prince was not always sure whether he could count on his own party’s loyalty. In secret David might have hoped to keep news of the accident from his father or postpone the moment of truth until he and the King had a private moment together. He certainly did not write to his mother about the accident. What the Prince’s anger also reveals is how important driving was to him. Constantly in the centre of attention, driving created some space that David desperately wanted to preserve. Having given it a second thought, the Prince of Wales explained himself in a much calmer letter to the King on 25 July, doing his best to defend his case:

“I can give you my absolute word of honour that I always drive very cautiously & sensibly & that I never take any risks. Both Major Cadogan & Professor Fiedler will I am sure bear out what I say, & so I think it very wrong that people should go & tell you that I do things which are far from true. Accidents may happen to the best & most careful driver in the world, as they may happen at any game or sport, & I don’t see why they should happen to me more than to any other person particularly as I am always so careful. Of course I have not been driving at all since I received your instructions not to do so, but I hope that you will perhaps reconsider this & give me permission to drive again when I tell you that it means a great deal to me out here. […] So I am asking if with your great kindness you will give me permission to drive my motor again. All I have said about taking great trouble & caution when I drive is absolutely sincere & true. I know you will not mind my writing all this, as you like me to tell you what I think.”

A couple of days later, the Prince had every reason to be overjoyed and relieved: „I received a charming letter from dear Papa giving me permission to drive my car again”, he wrote in his diary on 31 July, “he is kind & we now understand each other so well.” For the young Prince, driving a motorcar was less a means of representation than rather a mode of expression. That was something the King, familiar with an adventurous and at times risky life at sea, could acknowledge. The educational trip to Germany might not have stimulated the Prince’s cultural taste buds to the extent his royal parents and Professor Fiedler hoped for, yet it provided the British heir to the throne with the opportunity to travel miles and miles in a motorcar, an experience of personal freedom he seems to have thoroughly enjoyed. On a different note it certainly taught him a useful lesson in parent diplomacy.

Suggested Reading:

A King’s Story. The Memoirs of H.R.H. the Duke of Windsor, K.G. London, Cassell and Company Ltd., 1951

Grahame, Kenneth, The Wind in the Willows, New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913, on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/27805

König, Wolfgang, Wilhelm II. und die Moderne. Der Kaiser und die technisch-industrielle Welt, Paderborn u.a., Schöningh, 2007

O’Connell, Sean, The car and British society. Class, gender and motoring, 1896-1939, Manchester, New York, MUP, 1998

Wroughton, J., A student prince in Germany, in: History Today 28 (1978), p. 3-13

Ziegler, Philip, King Edward VIII: the official biography, London, Collins, 1990

The author is most grateful to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for permission to make use of material held in the Royal Archives, Windsor.