See also: Princes on the road

Mission Impossible: An Italian King in Spain

Maria-Christina Marchi and Richard Meyer Forsting

Amedeo was born in 1845, only a year after his brother Umberto, the heir to the Italian throne. Owing to the small age gap the two were raised together. Brought up away from the court, in the royal residence of Moncalieri, just outside of Turin, they were educated by an important military figure, General Giuseppe Rossi, in the traditional, military-focused, Savoia style. Both brothers were immediately integrated into a narrative, typical in the history of the House of Savoy, which emphasised military bravery and a strong sense of duty. At the age of five Amedeo became a member of the National Guard in the Aosta Battalion. The role of the soldier-prince suited him more than it ever suited his brother Umberto, and Amedeo quickly rose through the ranks – and not only because of his lineage. By 1861 the Savoia had united large portions of the Italian peninsula under their crown, and Amedeo was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel of the 5th regiment of the Aosta Brigade, was a Major in the same regiment, and Colonel of the 1st legion of Milan’s National Guard: all of this before he had even turned seventeen.

Before the battle of Custoza, on 24 June 1866, though, Amedeo remained a relatively unknown figure. Most of the royal propaganda was focused on turning his father, Vittorio Emanuele II, into a heroic figure, the “Father of the Fatherland”. The princes were slowly integrated into public life, with travels throughout Italy and the Levant which gave both Amedeo and his brother Umberto a little of the limelight, yet the popularity he would later experience in Italy was not yet apparent.

Bravery and duty: qualities of a king

The battle of Custoza was one of the defining moments during the Third War of Independence, which aimed to complete Italian unification. In an attempt to claim the Veneto for the Kingdom of Italy, Italian troops were sent to fight the Austrian enemy. The battle marked a brutal and humiliating loss for the Italian army, despite its numerical superiority. However, the damage to the military prestige of the monarchy was softened by the acts of bravery shown by the king’s younger son, Amedeo. Despite warnings from his generals, Vittorio Emanuele sent both sons onto the battlefield, claiming that “if we princes of house Savoia had stayed at home when our soldiers fought, then we would find ourselves like the Bourbons of Naples [a dynasty the Savoia had deposed in their battle for national unity]. I understand the interest you take in the life of the princes, but my sons are soldiers and they must fight.” (A. Trinchieri, ed., Amedeo di Savoia: Aneddoti, Appunti, Ricordi, 1890, p.11).

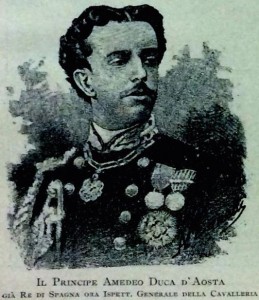

Amedeo was wounded in the battle, and although the bullet piercing his chest did not threaten his life, the injury meant he was hailed as a courageous warrior. He allegedly did not want to leave his men or the battlefield and had to be carried off by his aide-de-camp. Thereafter he refused any special treatment and insisted on other men being attended on before him. This selflessness and bravery earned him the golden medal “for the outstanding valour demonstrated by daringly leading, at the head of his brigade, the attack on the farmhouses occupied by the enemy at Monte Croce, where, amongst the first, he was injured by a bullet.” (Trinchieri, Amedeo di Savoia, p.14). The public response to his injury was overwhelming; he received numerous letters, and poems were dedicated to his bravery. There was a sense of gratitude for his personal sacrifice to the protection of the nation. According to one of his contemporaries, his biographer Augusto Trinchieri, the prince “exercised great charm on the people,” and was a loved figure of the Savoia family. These qualities turned him into one of the most promising Catholic princes in Europe. Not surprisingly he was high on the list of candidates when Spain began its search for a new monarch after ousting Isabel II in 1868.

From Amedeo to Amadeo

Initially both Amedeo and Vittorio Emanuele II refused the crown offered by Spain, which found itself in the peculiar position of being a constitutional monarchy without a monarch. The Italian heir was diplomatically the best option, because his election would not disturb the European balance of power. Having approached various internal and external candidates and caused a diplomatic row between Germany and France over the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen candidacy that ultimately led to war, the Spanish government once more looked to Italy. This time, Vittorio Emanuele pressured his son into accepting, in order to elevate the Savoia family’s prestige on the European stage. He had already married off his daughter to the king of Portugal, and to extend his family’s political reach could benefit the Italian royal house in the long run. Moreover, to place his son in an intrinsically catholic nation might garner some favour with the Catholic Church. Although it was said to be against his own wishes, Amedeo’s sense of duty towards his father and country were so great that he accepted the proposal, giving up his Italian citizenship in order to save a country that was not his.

Despite Amedeo’s qualities the Savoia’s conflict with the Vatican complicated his position. 1870 saw the annexation of Rome by the Kingdom of Italy, which made it the capital of the new nation state. However, Rome became a centre of double occupation, as the Holy Sea refused to acknowledge the city’s new status as “Italian.” The Pope acted like a prisoner within his own home, and although not actually treated as such, tension between the kingdom and the papacy was palpable. Over the years, September 20, the date of the breaching of Porta Pia and annexation of Rome, became an ambivalent event. On one hand it was commemorated by the state as the day when Italy was truly united as one, whereas for many Catholics in Italy and abroad it became a day of mourning. The most drastic step was taken by the Pope who excommunicated the Italian king after his conquest of Rome, “occupying” the seat of the holy pontiff. Some Catholic nations found it difficult to recognise Italy’s legitimacy in the light of what had happened. In Spain the Cortes, the Spanish parliament, was already troubled by the annexation of the Papal lands by the Italian army in 1865. To them Italy was born from “usurpation and a series of errors.” Therefore the conflict between the Savoia family and the Catholic Church was not a promising sign for the future monarch of Spain. The piety demonstrated by Amedeo’s wife, a Piedmontese noblewoman, Maria Vittoria dal Pozzo della Cisterna, and her struggle with her own king’s excommunication, was of some consolation, but the situation remained very complicated.

These issues notwithstanding, both the Cortes and the Italian parliament agreed to elevate Amedeo to the throne of Spain. The Cortes voted in favour of Amedeo as king (191 votes against 153) in November 1870 and on 4 December 1870 Manuel Ruiz Zorilla, president of the House of Deputies, and forty other Spanish delegates, conveyed the news of Amedeo’s election to Florence, where he was declared Don Amadeo I of Spain. Before leaving his old fatherland for his adopted patria, Amadeo already displayed an awareness of the difficulties he would have to face. He knew that not everyone would welcome him, that some would see him as a usurper and a foreigner. He was conscious of the difficulty of reigning in a politically divided country and he knew that he was “going to [Spain to] carry out an impossible mission.” The country was divided and he feared that it would “unite against a foreign king.” (Trinchieri, Amedeo di Savoia, p. 21). His predictions, it would seem, were to come true.

Amadeo: A new hope

Even before Amadeo’s election, the ultra-Catholic Carlist branch of the Spanish Bourbon family was preparing to press its claim to the throne once more. On 18 April 1870 an assembly at Vevey in Switzerland, composed of leading supporters of the Carlist cause, had proclaimed Don Carlos the new King of Spain. The creation of a Carlist ministry in exile and military appointments to positions within Spain foreshadowed the conflict that would beset Amadeo’s reign. Besides, Spain was already facing financial difficulties and had been fighting an insurrection in Cuba since 1868.

Despite the difficult situation in which Spain found itself, Amadeo’s election filled liberals with the hope that his reign would open a new chapter in the country’s history. There was a sense in the international press and indeed within Spanish liberalism, that Amadeo had the qualities to overcome divisions and become the constitutional monarch so hoped for by progressives in Spain. Thus The Times, in a report on the election of Amadeo, stressed his virtues: “The Duke [Amadeo] has sense, courage, tact, discretion, and that happy mixture of dignity and winning affability which covered a multitude of his father and his grandfather’s sins.” Progressive forces invested their hope in Amadeo. They wanted him to build a more positive and modern national identity based on progress, liberty and national sovereignty, far removed from the corruption and decadence that had come to be associated with reign of Isabel II. The famous historical novelist Benito Perez Galdos wrote of how one of his friends “saw in the King a new hope for the Patria”. Many echoed this feeling and had high expectations in their constitutionally elected monarch.

These high hopes were always going to be difficult to fulfil. Amadeo himself expressed his scepticism and seems to have been moved more by his sense of duty than optimism. In his acceptance speech he declared, “I accept the noble and lofty mission which Spain confides in me, although I am not unaware of the difficulties of my new task, nor of the responsibility I assume before history.”

An ominous start to the reign

Before he even arrived in Spain, Amadeo’s reign received a major blow. On the 30 December 1870 General Prim died of the wounds inflicted on him by unknown assassins the day before. This cowardly attack removed one of Amadeo’s key supporters in Spain. Prim had been one of the leaders of the 1868 uprising against Isabel II, a military hero of the African campaign and one of the key politicians of the post-revolutionary period. In the presentation of the candidature of the Duke to the Cortes on 3 November 1870, Prim had expanded at length on Amadeo’s merits. Furthermore he formed the coalition that delivered the 191-deputy majority voting for the Duke of Aosta in the tumultuous confirmation session of 16 November 1870. Prim had been one of the few politicians able to keep together the broad alliance of the 1868 revolution. Without his political direction Spanish politics became increasingly divided and Amadeo struggled continuously to nominate a stable government. His two-year reign saw eight governments and three general elections.

The new king’s task was made even more complicated by the attitude of the Spanish aristocracy. The nobility had always been the monarchy’s strongest supporter, but this support waned during Amadeo’s reign. The new royal family did not only induce suspicion for having been elected by the Cortes, but also lacked any roots in Spanish history. Amadeo and his wife were regarded as foreign monarchs, imposed on Spain against its traditions and ancient laws. Attempts made by Amadeo’s proponents to link the dynasty to the 1712 Treaty of Utrecht’s provision of the Crown passing to the house of Savoy in case of Philip V’s line failing, were largely unsuccessful. Furthermore the deeply Catholic grandees were offended by the conflict between the new Italian state and the papacy. The whole Savoy family was held responsible for the ‘captivity’ of the pope.

This rejection found its expression in public and private acts of defiance. One of the first examples of a public expression of the nobility’s discontent occurred when Amadeo arrived in Madrid for the first time. Galdos reports how the most important noble families of Madrid conspicuously refused to fly their banners and kept their windows shut during the official festivities in honour of the arrival of the new King. His wife Queen Maria Vittoria was another target of demonstrations of hostility. She first had difficulties finding suitable chambermaids, traditionally selected from important noble families, and was later publicly slighted by noble women displaying Carlist or Bourbon insignia.

The monarch of the people?

This experience of antipathy from the nobility further encouraged the royal couple’s natural inclination to forge a closer link between the monarchy and the people. Amadeo was known to go on walks through Madrid without any bodyguards, he travelled in open carriages and attended popular concerts and festivals. Before Amadeo came to Spain, there had been stories about his random acts of kindness in the streets of Turin. He continued in this vein even after an assassination attempt in July 1872; in a widely commented show of defiance he even returned to the scene of the crime the following day. Amadeo’s valour was not really in question. Queen Maria Vittoria was very active in her efforts to ingratiate the new monarchy with the people of Madrid. She used some of the allowance for her son’s education to fund a Kindergarten and school for washerwomen, as well as using her personal allowance to found an orphan asylum.

For some commentators this ‘popular touch’ amounted to a debasement of the monarchy. As the Republican Emilio Castelar argued in the Cortes, monarchy in Spain had always been based on mystery, pomp and ceremony, its “ability to represent the eternal glory of the nation.” The insistence on simplicity of the new monarchy certainly did nothing to win over his aristocratic enemies. However, it could be argued that any attempt to gain their allegiance would have been futile anyway. Unfortunately for Amadeo, the same was true for his ability to win over the mass of the population. As he wrote to his father in March 1872: “The masses, as I have already told Your Majesty, are Carlist and Republican. The clergy counts as completely Carlist and has great influence over the people living in the countryside. The aristocracy is for Alfonso.” As the king realised, the Catholicism of the masses and clerical influence put him on the back foot. There were few elements Amadeo could count on, undermining his reign before it even had a chance to take root in Spain.

“In Spain the army is everything and without the army one can achieve nothing”

One of the key players Amadeo needed to keep on his side was the army. The Spanish military had played an important part in politics ever since the uprising against Napoleonic rule in 1808 and had since then guarded its right to intervene in politics in the name of the national will. In 1872 it was engaged in two wars, one in northern Spain and the other overseas, in Cuba. The king was aware of the central role the army played in Spain, writing to his father that “in Spain the army is everything and without the army one can achieve nothing.” Amadeo’s bravery in battle and military education probably helped his standing within the army but he had to admit to his father that “the army is where the Alfonsino sentiment is abundant.” This view was confirmed by the American minister to Spain, who in June 1872 reported that “several battalions of the army have been gained over to the cause of the Prince Alfonso”.

The situation was further accentuated by the conflict over administrative reform and slave emancipation in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The powerful colonial interest groups formed into a league and together with several newspapers agitated against any notion of colonial reform. They counted among their supporters some important members of the military establishment. This clashed directly with Amadeo’s support for the government’s plans for the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico, signed into law by royal decree on 23 December of 1872. As Carmen Bolaños Mejías (El Reinado de Amadeo de Saboya y la Monarquía Costitucional, 2014) has argued the mobilisation against these measures prepared the ground for the conflict with the army that finally led to Amadeo’s abdication.

The tension within the army reached a critical point when General Baltasar Hidalgo was appointed to a key post in the Northern Army. The choice was highly unpopular and Amadeo unsuccessfully tried to dissuade the Minister of War from making the appointment. Almost immediately the entire Artillery corps resigned in protest and demanded to be relieved from duty. There were suggestions that they pushed towards to this drastic step by colonial pressure groups. H. Whitehouse, the secretary of the United States embassy in Italy at the end of the nineteenth century, even suggests that they continued to receive their salary through the anti-abolition league. It was feared now that in the middle of two wars there could be further defections. Amadeo signed a decree for the dissolution of the artillery corps presented to him by Ruiz Zorilla, the president of the council of ministers, but the king simultaneously informed him of his determination to abdicate. He could have forced a change of ministry by blocking the appointment of Baltasar Hidalgo or refusing to sign the decree of dissolution, which sections of the army openly urged him to do. The colonial pressure groups probably expected him to name a more conservative ministry and when he abdicated and the Republic was declared, they had to realise that they had overplayed their hand.

Amaedo was unwilling to rule outside the limits of the 1869 constitution. He kept faithful to his declaration on the opening of the Cortes in April 1871, when he declared that “Within the constitutional limits I shall govern with Spain and through Spain, through the men, the ideas and tendencies which are legally suggested to me by public opinion as evinced by parliamentary majorities – the true regulators of constitutional monarchies.” As Varela Suanzez-Carpenga has argued (“La monarquía en las Cortés y en la Costitución de 1869,” Historia Costitucional 7, 2009), one of the key problems was that the rigging of elections meant that the constitutional theory and practical political realities did not necessarily coincide. The crisis of February 1873 would have demanded a more active involvement of the King, which would, however, have meant breaking with the constitution. As Alicia Mira Abad has shown, Amadeo was never prepared to do so, declaring that looking for solutions “outside the Law should not be sought by those who promised to uphold it.” (Secularización y mentalidades: el Sexenio democratic en Alicante (1868-1875), 2006). In the end it was a sad indictment of the political situation Spain found itself in, that two of the main causes of the downfall of Amadeo were his willingness to press on with a law abolishing slavery and his unwillingness to break with the constitution.

Amadeo was not above admitting his failure, despite having battled bravely in the face of what must be considered almost insurmountable odds. In his abdication letter he expressed his frustration: “I realise that my good intentions have been in vain. For two long years I have worn the Crown of Spain, and Spain still lives in continual strife, departing day by day more widely from the era of peace and prosperity for which I have so ardently yearned.” The mission he was charged with, was impossible for him to fulfil, as he himself had to ultimately concede: “I am today firmly convinced of the bareness and the impossibility of realizing my aims”.

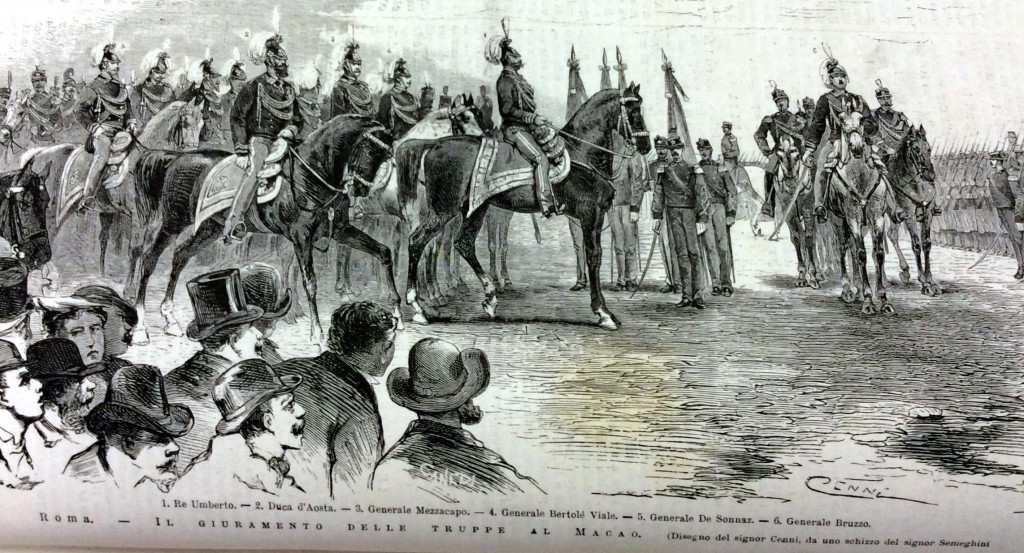

Amedeo reviewing the troops with king Umberto I on the king’s birthday, Illustrazione Italiana, Anno V, N.11, 1878

The return of the king

“I now beg your Majesty to grant upon myself and my sons the Italian nationality, that I lost when I accepted the crown of Spain. I take the liberty to remind you what I have lost in Italy by accepting this crown.” So Amedeo wrote to his father upon departing Spain and leaving a crumbling nation behind. His efforts had failed and his only desire was to return home, to divest himself of the crown and become once again the Duke of Aosta. His mission had failed but his honour remained intact.

Amedeo visiting the Cholera-stricken poor in Naples with Umberto, Illustrazione Italiana, Anno XI, N. 26, 1884

He returned to his royal duties in Italy with much ease, acclaimed for his efforts abroad, for his Spanish “adventure.” He was warmly welcomed back by the government. The Prime Minister Marco Minghetti stated that “Italy… loves this Prince. He fought for us. And today we welcome him with affection.” Another member of parliament, Francesco Crispi, reportedly added that, “[some of us] were opposed to the acceptance of this crown; but today we are immensely pleased not for the painful turn of events, but to see a Prince that chose the best of options, abdicating a throne where he could not reign in the name of freedom.” Reintegrated into the Italian royal family and granted back his title and position as general lieutenant, Amedeo was reintegrated into Italian life without much difficulty. He represented his brother the King of Italy on numerous important occasions, at state events, leading military manoeuvres and travelling extensively with Umberto.

When he died in January 1890, the nation mourned a hero and a prince. His early demise was seen as a consequence of the heartbreak that Spain had caused him. Not only had his first wife, Maria Vittoria, died soon after their return to Italy – a death largely attributed to the stress she had endured as queen – but Amedeo also felt that he had failed in his mission to help Spain rise from the ashes of the 1868 revolt. And this he could not forgive himself. However, his disappointing rule in Spain was seen by the Italian masses as a valiant attempt to spread the Savoia’s sense of freedom, and his return was not seen as failure, but rather as a homecoming. His bravery and presence at his brother’s side became his distinguishing features and his short rule in Spain was soon forgotten.

Suggested Further Reading:

Bolaños Mejías, Carmen, El Reinado de Amadeo de Saboya y la Monarquía Costitucional, (Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educacion a Distancia, 2014).

Mellano, Maria Franca, I principi Maria Clotilde e Amedeo di Savoia e il Vaticano (1870-1890), (Torino: Centro Studi Piemontesi, 2000).

Pí y Margall, Francisco, El reinado de Amadeo de Saboya y la república de 1873. ([Madrid: Seminarios y Ediciones, 1970)

Speroni, Gigi, Amedeo d’Aosta: Re di Spagna, (Milano: Rusconi, 1986).

Trinchieri, Augusto, ed., Amedeo di Savoia: Aneddoti, Appunti, Ricordi, (Roma: Forzani E C. Tipografi del Senato, 1890).

Whitehouse, H. Remsen, The Sacrifice of a Throne, Being an Account of the Life of Amadeus, Duke of Aosta, Sometime King of Spain, (New York: Bonnell, Silver & Co., 1897).